New Zealand children’s author Ronda Armitage wrote the much loved The Lighthouse Keeper’s Lunch in 1977.

While she imagined industrious Mr Grinling polishing his light and Mrs Grinling concocting delicious lunches for him, Paul Trevethick was labouring in Plimmerton about to spy a newspaper advert for a relieving lighthouse keeper with “an ability to cook and tend for themselves under isolated living conditions.”

His first assignment was to The Brothers in Cook Strait to be winched ashore by crane and find “good free food, television, a telephone, blue cod galore, storms and clear, clam days.” The New Zealand ensign was hoisted to mark the marriage of Prince Charles and Diana, while hot-smoked blue cod, squid in beer and tomato sauce and butterfish poached in vodka found their way onto the menu.

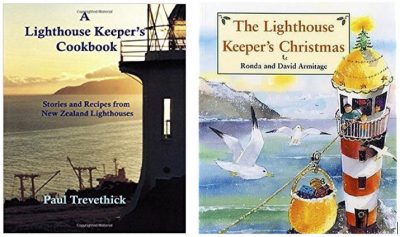

Trevethick made eight visits to The Brothers while a relieving lighthouse keeper over seven years. In A Lighthouse Keeper’s Cookbook: Stories and Recipes from New Zealand Lighthouses he recounts tales from his time at 10 lighthouses with recipes from each.

At Nugget Point, surrounded by seals and yellow-eyed penguins, he goes on a vegetarian binge and whips up Grilled Brie and Almonds, Mulled Cheddar Soup and Stir-Fried Bean Sprouts.

While Mrs Grinling’s “terrible happening” was seagulls stealing lunch from the basket as it ran along a wire from the cottage to the light, Trevethick’s incidents are more serious.

He was on duty at Baring Head when the Pacific Charger ran aground below the light in 1981. The scene provides the cover image of the book in a format that echoes Armitage’s children’s series.

At Puysegur Point, a resupply ship delivers diesel and coal but forgets stores and mail and a helicopter needs to be called in – “a thousand dollar mistake.” Hunters, fishermen and few lost souls drop in at the Fiordland station providing tales of adventure and ingredients for several venison, paua and crayfish recipes.

In the Hauraki Gulf, Trevethick is assigned to the Tiritiri Matangi light and recalls the character and resourcefulness of Ray Walter and family, who go on to organise ‘the spade brigade’ and restoration of the island as a wildlife sanctuary. It’s also an opportunity to remind us of the bureaucracy of the time, with a list of 32 Standing Orders for Lightkeepers, to be reported monthly.

At Tiri he serves up oyster and kumara pie, raw fish with wasabi sauce and home-made Kahlua. From another Gulf island, Cuvier, it’s black pudding burger, drunk sheep with coconut beans and mince on toast.

The recipes – indicated as “my invention”, “adapted” or “an old family recipe” – may not all be as mouth watering as Al Brown’s creations but Trevethick’s intent for the book is more than culinary. It serves as a potted history of lighthouse keeping in New Zealand, reminds us of the attitudes of the 1980s and its public service quirks.

There’s enough “good sticks”, “dipshits”, “smart-arses”, “arrogant bastards” and “pricks” to populate a Barry Crump novel.

But by the end of the Eighties it’s the “arrogant, bull-headed Governments and cold-blooded technocrats” that usher in automation to “get rid of the pesky, unfathomable, lucky rogues who lived on beautiful, remote coastal parts of the country.”

Trevethick though has read the signs, fallen in love with “a very attractive, intelligent lady”, scored a job with the Meteorological Service and eventually goes on to become a chef “in good stead from cooking all manner of meat and seafood on lighthouses.”

Treats from the times indeed.

Paul Trevethick now lives at Waikino near Karangahake Gorge in the Hauraki District and his self-published A Lighthouse Keeper’s Cookbook: Stories and Recipes from New Zealand Lighthouses is available from lh.keeper@hotmail.co.nz