Shorebirds are important members of the Tāmaki Estuary ecological community. Several species are considered important taonga (treasures) by Māori.

Many species of shorebirds are capable of epic migrations across the planet and were valuable navigators to early wayfaring Polynesians, guiding them to whenua like Aotearoa.

These birds have utilised the rich feeding grounds of the Tāmaki Estuary for thousands of years, roosting on the edges of the awa (river / estuary) and even rearing their offspring here. The abundance and resources and (formerly) lack of predators meant that the Estuary historically supported an incredibly diverse array of bird species with large populations.

This abundance is referenced in nearby Māori place names such as the Manukau Harbour, which lies due west of the Tāmaki. According to the history of some iwi (Māori tribes), this area was named for the immense populations of shorebirds that greeted the first waka with their deafening calls.

Unfortunately nowadays, shorebird populations in places like the Tāmaki Estuary are a ghost of their former status.

It is unclear how many species formerly called this place home, but we do know of several local extinctions including Ruddy Turnstone, Golden Plover, and Lesser Knot.

At least 21 species still occupy the Tāmaki Estuary, including critically endangered species like Shore Plover. Some species occur year-round, while other migratory species are intermittent residents. However, many of the remaining species are at risk of disappearing from the Estuary all together. There is now concern that the Tāmaki Estuary might become New Zealand’s first estuary with no shorebirds.

In his 2019 report titled Shorebirds of the Tāmaki Estuary environmentalist and Tāmaki local Shaun Lee highlights the current trajectories for shorebird populations in the estuary, as well as the mechanism behind those trends:

“Steep declines have been recorded for migratory wading birds, gulls and shags. Degradation and just complete loss of roosting areas is the most likely cause for declining shorebird numbers.”

Shaun Lee (2019).

Roosting is ‘bird talk’ for sleeping or resting. A lesser-known fact about shorebirds is that many cannot roost in trees. In the case of species like South Island pied oystercatcher and the conservation dependant New Zealand Dotterel, large flat open areas near to water with no line-of-sight impediments (e.g. trees) such as the sand spit at Tahuna Torea Nature Reserve and the grassy areas at Point England are preferred roosting habitat.

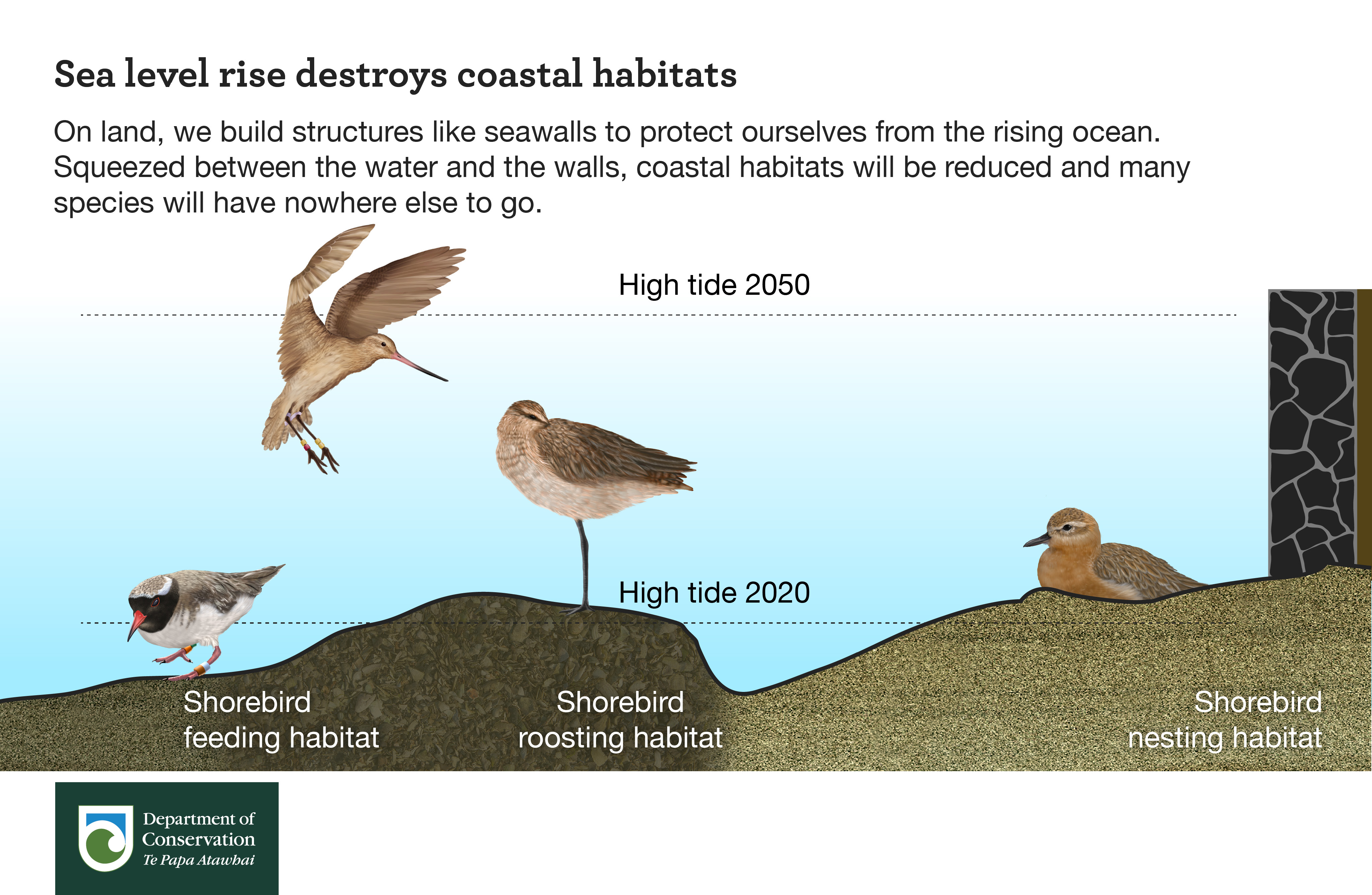

These roosting habitats are facing pressure from all sides – both on land and from the water. King tides and storm surges have diminished roosts at Tahuna Torea over the years, which has been exacerbated by erosion of the sandspit. And as the human population continues to encroach upon the coastal environment, these roosting areas are likely to disappear under buildings, roads, cycleways and footpaths.

The loss of roosting habitat has been so extreme in the Tāmaki Estuary that some birds are now using large industrial metal roofs in Penrose. It is unclear how this shift in behaviour affects the health of the bird population, however it is thought that the increased distance from feeding grounds in the estuary is likely having a negative impact.

As birds change their behaviour in response to a range of anthropogenic pressures, it is likely that the functional role of these species in the ecosystem will be impacted.

For example, at low tide shorebirds feed in the estuary mudflats, pecking and probing for prey such as insects, worms, and crustaceans. This disturbance created by the collective feeding action of birds allows for essential nutrient cycling and improves oxidation of the estuary substrate, the net benefit being the improvement of subsurface habitat for a range of fauna and flora.

If shorebirds are not performing their role within ecosystems, we may see even sharper declines in the overall health of the Tāmaki Estuary marine environment.

The plight of the Tāmaki’s shorebirds is a key focus of the Tāmaki Estuary Environmental Forum (TEEF), who are committed to ensuring that these birds will continue to be around for generations to come. TEEF has sponsored shorebird surveys in prior years, teaming up with experts and other groups including Birds New Zealand .

TEEF participants continue to advocate through a variety of channels for a linked-up management approach when it comes to maintaining and preserving critical habitats for these birds.

TEEF is optimistic that the decline of the Tāmaki shorebird population can be reversed. However, given the severe spatial constraints on natural and semi-natural roosting habitat which are unlikely to alleviate in the future, innovative solutions such as floating artificial roosts should also be considered. Exploring ways in which these engineering interventions interact with and complement mātauranga Māori perspectives on wildlife management represents an exciting pathway for both the community and government organisations to develop effective co-management with local iwi.

Key partners including Māori, Auckland Council, Local Boards, community volunteers and central government departments continue to be important stakeholders in this kaupapa.