Odette Howarth is a PhD candidate at the School of Natural and Computational Sciences, Massey University. Recently, we had a chat about the research she is conducting on fish in the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park / Tīkapa Moana / Te Moananui-ō-Toi.

What are you studying and why?

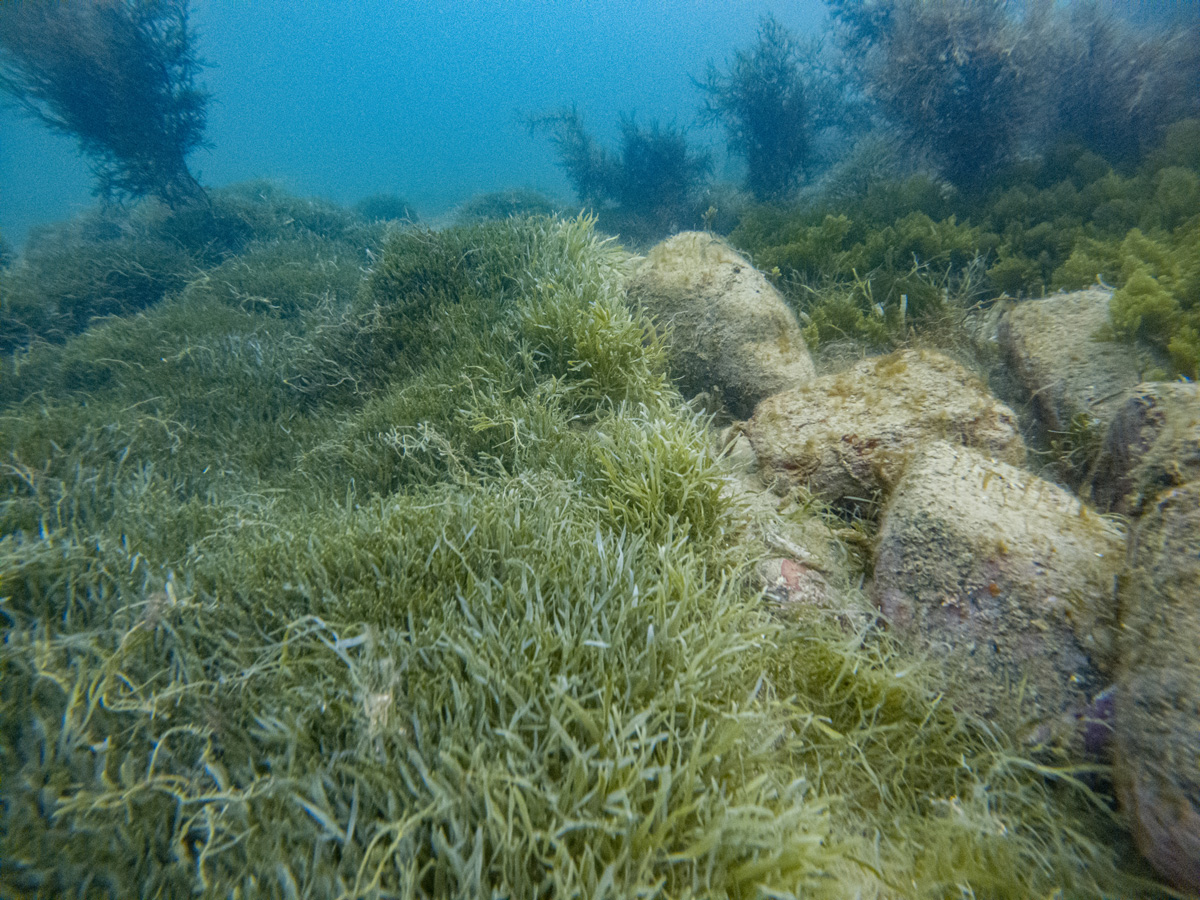

I am taking baseline data on fish specifically their diversity, abundance and assemblages (the range of species in the same area at the same time). I am also looking into why they are using the habitat (e.g. food, shelter). The areas I am sampling are from inside and outside of the areas that are proposed to be protected in the Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari Marine Spatial Plan, such as Rotoroa, the Noises, Motutapu and Te Hauturu-o-Toi/Little Barrier Island. By taking this baseline data and providing a better understanding of what’s going on in these areas, it will help with future monitoring and management.

During my research, I have also travelled to Fiordland where Marine Protect Areas (MPAs) are already established to take data from inside and outside of the areas too. By comparing established MPAs and surrounding areas we measure the reserve effect on the populations of fish species over time.

You are using a data collection tool called ‘BRUVS’, can you tell me what BRUVS is?

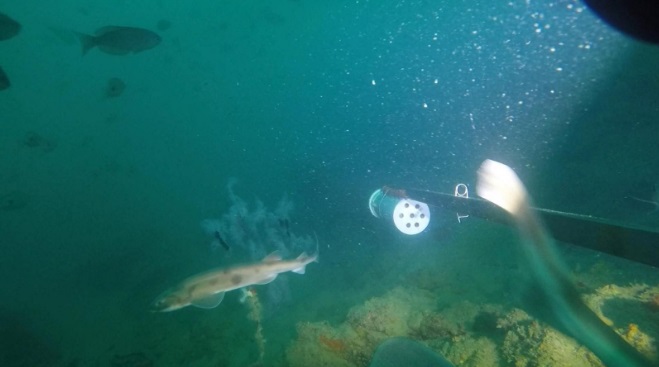

Baited Remote Underwater Video Stations (BRUVS) records high definition underwater video of marine life that are attracted into the camera’s field of view through using a baited pole.

By collecting underwear video, I can conduct statistical analysis to compare areas for abundance and assemblage of fish. The software I use gives really accurate measurements which also enables me to obtain morphological and length data to understand the age classes of the fish using the area.

We are also able to test variables such as water depth and reef exposure to understand which species use certain areas. For example, along with the coastal reef areas that I have sampled, I have also been collecting data at mesophotic reefs. Mesophotic reefs are found where the light penetrating waters meets the darker, deeper waters of the ocean – this is at around 60-120m in the depth. These depths are generally really quite hard get to and study, so it is allowing me to collect data on rarely studied areas of the ocean ecosystem.

Using BRUVS will aid with continued monitoring once MPAs are brought in so we can determine over time whether things like age class ratio or fish diversity changes.

Why is BRUVS a good tool to use?

BRUVs is non-invasive, has minimal impact on the environment and it also allows to collect data for longer. This sets it apart from traditional methods like trawling and diving.

By having minimal disturbance, our cameras are basically spies providing us with a more natural insight in the marine world. We have been able to pick up on the small and cryptic species that you rarely seen because they are so secretive and sensitive to changes in their habitat. We’ve also captured species that are not attracted to the bait and are just passing through the area, such as butterfly perch whose distribution is much larger than the reef we filmed them on. This gives us a better idea of the overall biodiversity of an area as opposed to a singular snapshot in time which is generally what happens with the other methods.

Alongside the data collection benefits, the videos we obtain are also a great way to engage with an audience – it has been proven to be an effective science communication tool!

What interesting or surprising things have you found so far?

Through my data collection, we’ve discovered certain deeper areas of the Gulf which seem to be a middle ground between the areas that are fished recreationally and those fished commercially. The data from this has shown that because these areas aren’t typically targeted, the fish and invertebrate species found there can be super interesting. Some of the things we have found you wouldn’t necessarily expect for Auckland waters such as black coral and a blue cod population!

You are also a Wildlife Technician at Massey University, supporting with teaching and others with their research. What else have you been involved with?

When I’m not collecting my own data, I’m usually teaching or assisting others with their research. This has included necropsies on marine mammals and seabirds to understand the species that live and utilise the marine park, tissue sampling of sharks, tagging of school sharks in the Kaipara Harbour, collecting kelp samples for testing anthropogenic stressors and even 3D printing of animals for collections!

Fantastic! So, what’s next?

I have about 3.5 years left of my PhD so I’ll be continuing to collect data and start writing up my thesis! This summer we plan to collect data at the Mokohinau Islands and the Poor Knights looking at fish that inhabit different depth gradients. By comparing an MPA and non-MPA we can start to tease apart whether fish species assemblage at depth is different inside and outside protected areas.