Sound travels exceptionally well in the ocean’s vast expanse, conveying a wealth of information to marine animals about their surroundings. Unfortunately, however, many underwater soundscapes are being polluted by noise generated from human activities, such as commercial shipping, seismic exploration, and deep-sea drilling. The additional noise in the soundscape can have dire consequences for marine animals that rely on their hearing, as missing acoustic signals could mean the difference between life and death.

Science has demonstrated the masking effect of ship noise on the communication space of marine mammals. Still, little attention has been given to the racket caused by small recreational boats in coastal waters.

In new research published this year, University of Auckland researchers assessed the impact of recreational boat noise on the Hauraki Gulf soundscape. They analysed acoustic recordings at three popular recreational boating areas and two no-take marine protected areas (MPAs).

The study shows that the sound of small boats is pervasive in the Gulf. The noise is also a cause for concern within MPAs, which should provide wildlife refuge from all human stressors.

The study has provided novel evidence that small boats are a significant source of noise pollution in the Gulf and likely at other populated shallow coastal regions worldwide. Moreover, the findings have highlighted the necessity for policy to mitigate the impact of sound from small boats on wildlife, particularly ensuring adequate protective measures around designated marine reserves.

Quantifying recreational boat noise

Sampling from several sites is necessary to capture the variation of artificial sound in the soundscape. Therefore, researchers collected acoustic recordings from five morphologically and geographically distinct areas to better understand the aural picture painted by recreational boats.

Researchers gathered acoustic measurements from Kawau, Tiritiri Matangi, Ōtata Islands, Goat Island Marine Reserve, and Tāwharanui Marine Reserve.

The National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research identified the first three sites as high-pressure recreational boat sites in 2017. In comparison, both marine reserve sites are strictly no-take protected areas.

The researchers combined the acoustic recordings with information about the environment in models to determine patterns in boat noise within the soundscape.

The recreational racket of small boats

Researchers detected boat sound almost every day at all sites. Boats were generally most active during daylight hours. Overall, boats made the most significant acoustic footprint on the soundscape during summer.

However, there were some distinct differences in sound patterns between sites. For example, boat activity was lowest at Goat Island (71% of recordings contained boat sound) and was the only area where boat activity was higher at night. In addition, boat noise only significantly impacted the low-frequency portion of the soundscape during summer. In comparison, a whopping 98% of recordings from the Kawau site contained boat noise, and they made a significant racket throughout the year.

The researchers found that areas closest to Auckland contained the steadiest hum of that boat noise, i.e., the highest proportion of recording files with boat sound. However, boat sound had the most impact at sites closest to boat access, such as ramps and harbours.

The results also make sense when put into the context of the purpose of the boat trip. For example, a previous study found that over 60% of recreational boats were “gone fishing” between 2011 and 2014. Since fishing is prohibited at Goat Island and Tāwharanui, fishing boats are more likely to head elsewhere, such as Kawau and Ōtata.

The impact of boat sound on marine wildlife

While there was little reprieve from boat sound in the Gulf’s underwater world, the impact of boat sound was most apparent during summer. It significantly increased the low-frequency portion of the soundscape. The timing is of particular concern as science shows that many fish species rely on acoustic signals as a prompt for reproduction during summer.

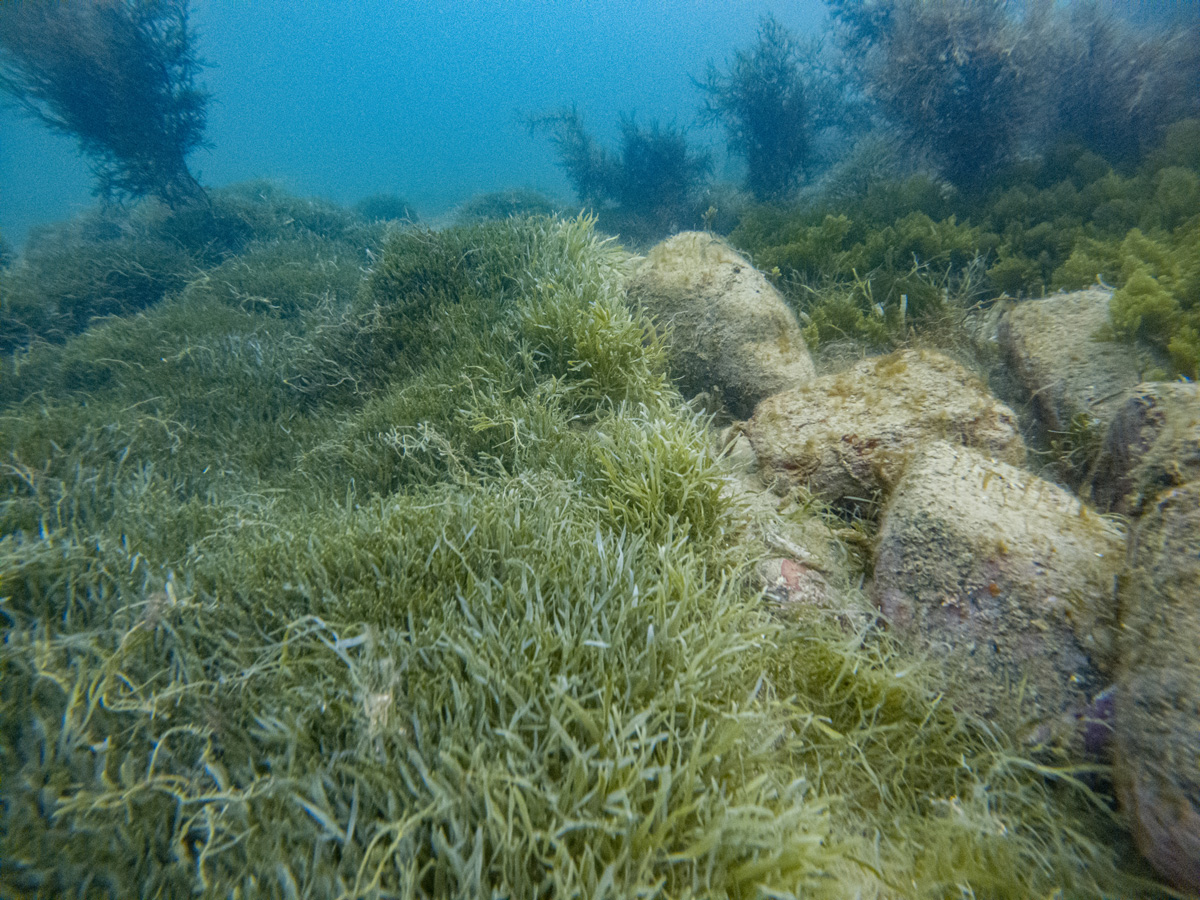

In addition, boat noise was loud enough in summer to drown out naturally occurring noises in the soundscape below 2kHz, which overlaps with the hearing and vocalisation range of fish, marine mammals, and crustaceans. For example, bigeyes are a nocturnal fish common throughout the Gulf’s shallow coastal habitats that rest in rock crevices during the day. In a previous study, researchers discovered that resting bigeyes make popping sounds below the range of 2kHz while at rest during the day to keep the group together.

Overall, this study demonstrates that small boats collectively make enough noise to mask animal communication and other critical acoustic cues, such as the presence of an incoming predator.

Redirecting the boat noise

Noise pollution affects natural soundscapes on land and sea, but there are ways to minimise the impact. The most apparent strategy here is to develop policies that mitigate the effects of boat noise on the soundscape, especially in ecologically rich regions and in areas where boat noise hits the hardest.

Boat restrictions are currently only written into the framework of around half the world’s MPAs. This research illustrates that current regulations do not protect animals in the Gulf’s MPAs from the noise pollution generated by small boats. Implementing measures that create a sound barrier around MPAs is necessary to protect these animals from all sources of human stress.