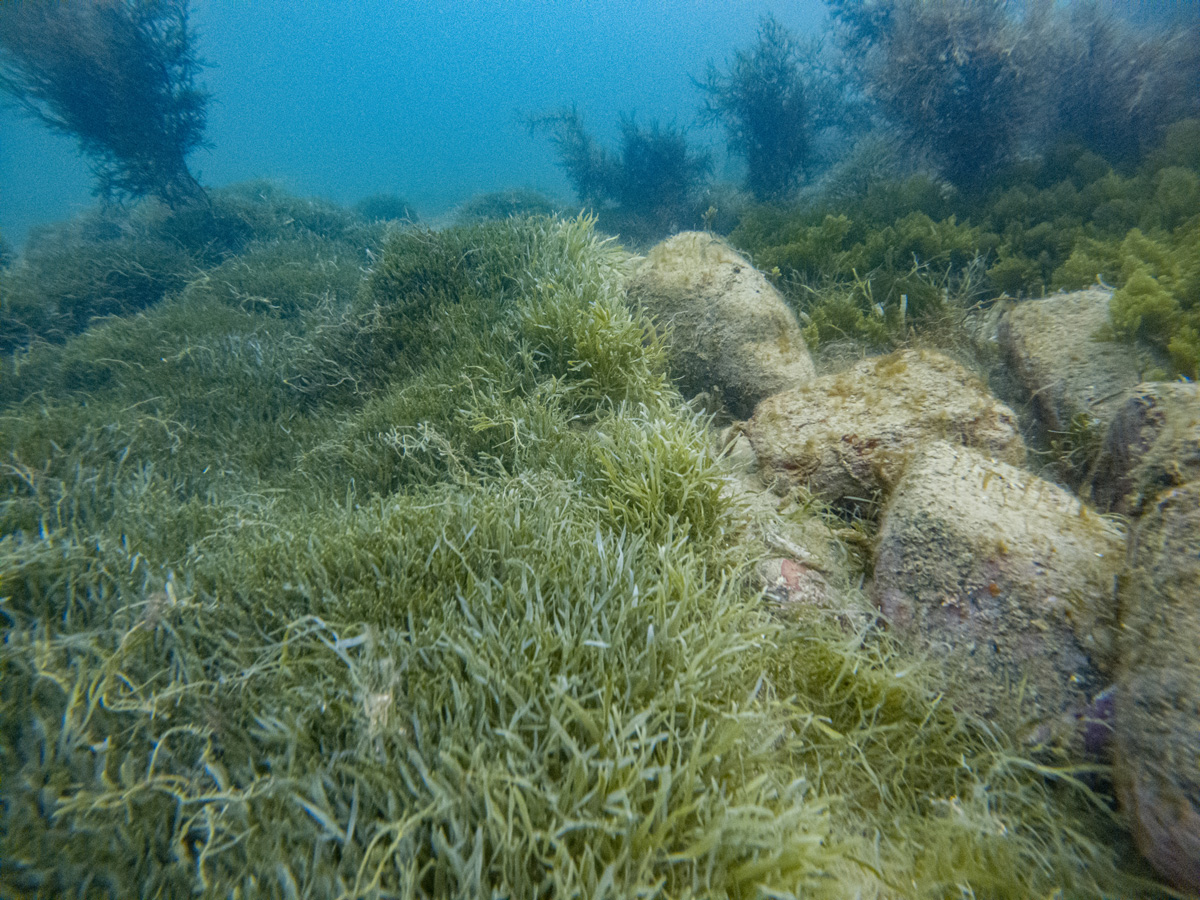

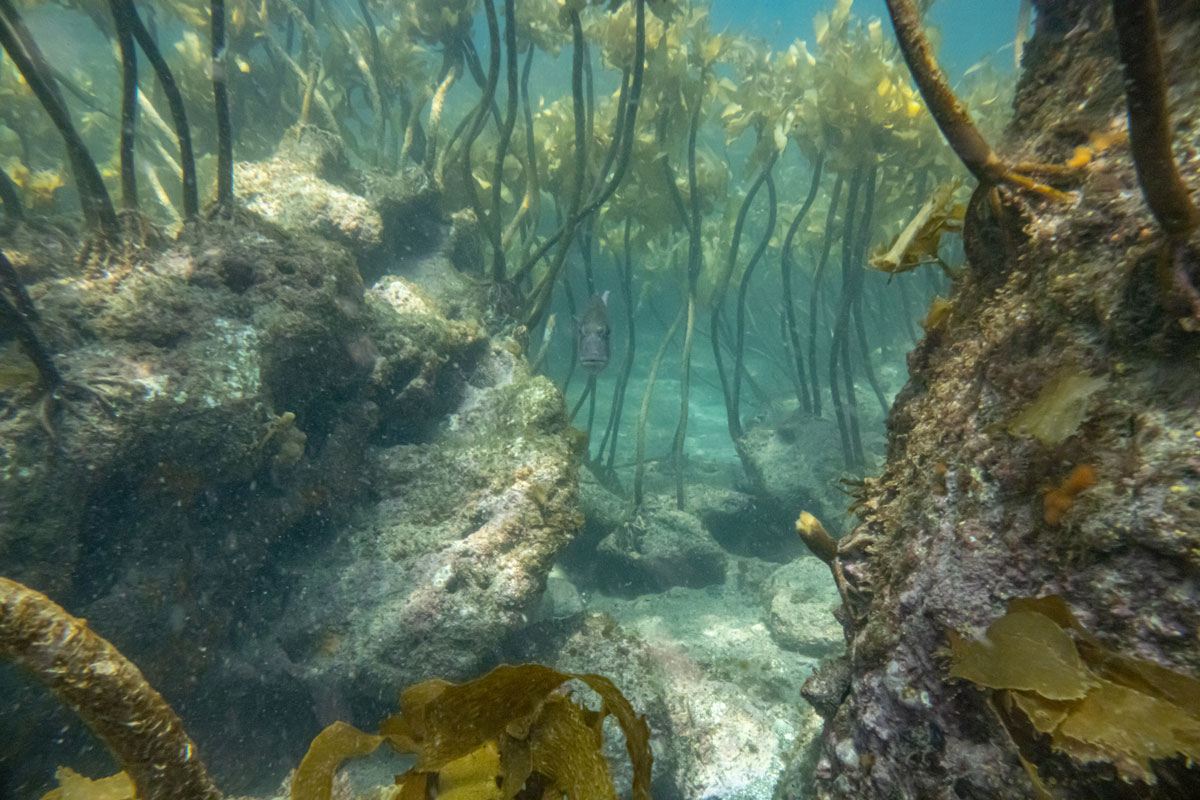

Kelp – a collective term for large brown algae species – are the trees of cooler-temperature coastal seas. They form the basis of rocky reef ecosystems and are a critical habitat for a diversity of marine life. Overfishing has taken a significant toll on kelp forests in the Hauraki Gulf/Tīkapa Moana/Te Moananui-ā-Toi. Kina (sea urchin) populations have boomed in the absence of healthy populations of their natural predators – snapper (tāmure) and rock lobsters (kōura) – and they have grazed away large extents of kelp forests. Kina barrens now dominate large parts of the coast. Habitat loss of this type has a detrimental impact on biodiversity and ecosystem functioning and adverse cultural, social, and economic impacts.

Kelp forests are keystone species and contribute to human wellbeing

Kelp (rimurimu) forests are among the most productive natural ecosystems and are a key habitat type in the Hauraki Gulf. Common kelp (Ecklonia radiata) is the most abundant species in our kelp forests. It is a keystone species as its forests provide food, shelter and habitat to various invertebrates, fish, and marine megafauna either permanently or at different life stages and ages.

Kelp forests are not only crucial to marine life – but they are of significant value to us land-dwelling humans, too, as they supply us with a range of ecosystem services that contribute to our wellbeing. For example, kelp forests clean the water of excess nutrients and afford shoreline protection to coastal communities by functioning as a storm barrier. Māori have a strong whakapapa relationship with kelp through their long history of harvesting seaweed as food.

Kelp plays into our economy both directly and indirectly. Kelp habitat is vital for replenishing populations of commercially and recreationally important species. It is a popular destination among divers and snorkellers and therefore is essential habitat for our marine ecotourism industry. In addition, seaweed extracts have a range of viable commercial applications. Kelp is also highly efficient at sequestering carbon and has gained attention as a potential mitigation and adaptation tool for climate change.

Kelp restoration in the Gulf

While the historical extent of kelp forests in the Gulf is unknown, large regions have been replaced by kina barrens. For example, approximately half of kelp forests have been replaced with barrens in the shallow reefs of Hauturu-o-Toi/Little Barrier Island and Ōtata. The good news is that various approaches and tools can restore the kelp habitat and its ecosystem services. It is currently an active area of ongoing research and the focus of many restoration initiatives.

No-take marine reserves are a tried-and-true approach to restoring kelp forests, evident in Goat Island Marine Reserve (Cape Rodney/Okakari Point Marine Reserve). No-take marine reserves deal with the root of the problem by eliminating fishing within the region. Snapper and rocky lobster populations recover in these “safe zones”, which reintroduces the effect of predation pressure on kina. This has a knock-on effect on flora and fauna communities; long-term monitoring in Goat Island Marine Reserve shows that kelp forests have replaced kina barrens. There have also been changes to the reef fish assemblages in part due to this protection. Marine reserves have a positive impact on recreational and commercial fisheries by resulting in a “spill-over effect” when animals targeted for fishing emigrate outside of the reserve’s boundaries following population recovery.

Removing kina from barrens is another approach to kelp restoration. The process of natural regeneration of kelp forests can be slow because of behavioural and physiological adaptations of kina, which effectively allows them to survive on less desirable food types and sit tight for decades. Kelp Gardeners – a community-driven restoration and education initiative – have been trialling this approach near Enclosure Bay and Palm Beach on Waiheke Island. They either relocate kina outside the pilot sites or gather and distribute kina to the local marae and community kitchens. Kelsey Miller at University of Auckland has worked closely with Ngāti Manuhiri to evaluate large-scale kina removal in the Hauraki Gulf for her doctoral research. They have been removing kina at four sites in the Gulf (7.1 ha total in total) to determine its value as a tool for kelp restoration. Preliminary results show promising signs that the approach effectively speeds up the process of kelp regeneration. Kelsey’s findings will have important implications for managing future marine reserves in the Gulf.

While no-take marine reserves and kina removal address the issue of kina barrens to restore kelp forests, seaweed farming can restore the ecosystems services they provide e.g., carbon sequestration and cleaning of the water, as well as have positive cultural, social, and economic outcomes. A pilot study is underway in the Hauraki Gulf and Bay of Plenty to establish an economically viable “seed to sale” seaweed sector using a regenerative ocean farming model developed by GreenWave US in America. The pilot is a considerable collaborative effort between the University of Waikato and University of Auckland researchers, Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki, local farmers, EnviroStrat, Auckland Council, and the Ministry for Primary Industries. The seaweed farming sector is a multi-billion-dollar industry in Asia but is new here in Aotearoa New Zealand. If all goes well, the pilot could mark the onset of a lucrative industry and new job opportunities.

Embracing Māori knowledge and traditions will be critical to the success of implementing regenerative ocean farming and more widely restoring the mauri of the Gulf. We have a lot to learn from kaitiakitanga –this tikanga (Māori value) has long encompassed the idea of sustainability through guardianship and conservation of the natural world. The use of rāhui to temporarily close certain types of fisheries, like the one placed on rock lobsters, scallops (tipa), mussels (kūtai), and abalone (pāua) around Waiheke by Ngāti Pāoa, will help kelp forests to recover.

Kelp restoration is a group effort

Kelp restoration involves many approaches and tools. Our journey with kelp restoration has only just begun in the Gulf – and our success hinges on the ongoing collaboration and cooperation between stakeholders.