Over the past several decades crayfish (spiny rock lobster, Jasus edwardsii) populations in the Hauraki Gulf have been in a serious decline. In 2016 the population of crayfish, known locally as kōura, in the Hauraki Gulf was deemed ‘functionally extinct’. This doesn’t mean they are all gone however the numbers of these popular crustaceans have fallen to levels where they are no longer able to keep kina numbers in check, a big part of their role in the ecosystem.

Recorded catch-per-unit-effort (CPUE) in the fishery, CRA2 in northeastern New Zealand, tells a similar story of decline. CPUE is a measure of how easy it is to catch the particular species. In short, crayfish are becoming harder to catch and each one caught requires more effort.

A recent study featuring the work of several marine scientists from the University of Auckland, reveals that crayfish numbers are even declining in our no-take marine reserves in the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park.

Why would crayfish populations in marine reserves decrease?

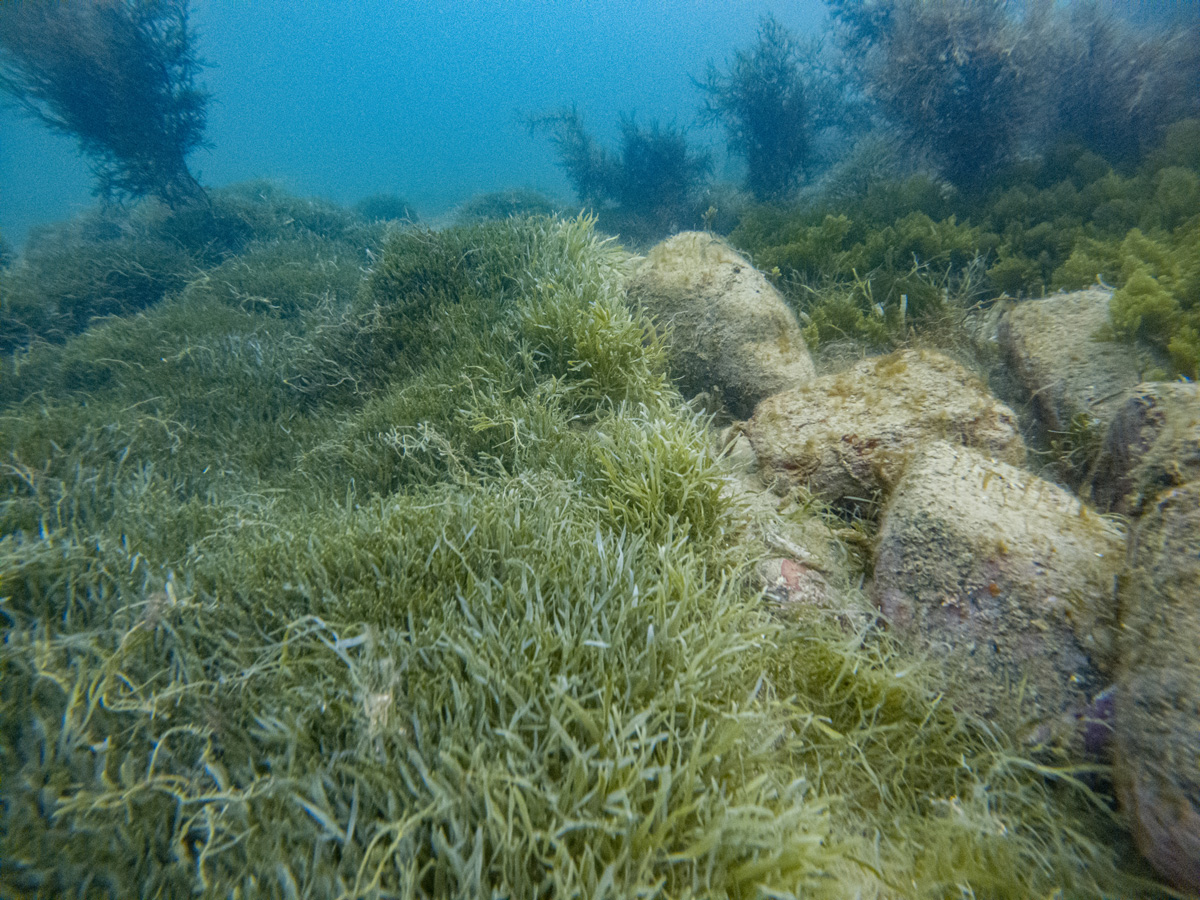

Scientific divers from University of Auckland and consultants through the Department of Conservation have carried out underwater visual censuses (surveys completed using SCUBA) to monitor crayfish populations in our marine reserves for decades. For populations in our reserves we have a great data set which dates back to 1977 – an incredible 45 years of data.

Surveys in three of the Hauraki Gulf’s reserves were carried out annually to investigate the numbers of crayfish in the Cape Rodney-Okakari Marine Reserve (5.2 sq. km) the Tāwharanui Marine Reserve (3.9 sq. km) and the Hahei Marine Reserve (8.4 sq. km). Crayfish in all of these reserves benefitted at first, with crayfish numbers in marine reserves increasing significantly with reserve protection compared with the populations of crayfish in neighbouring fished areas. However, over the past decade there has been a steep decline in populations inside the reserves as well.

One big factor is fishing pressure at the boundary of the reserves, which can affect the populations within protected areas as crayfish can move seasonally and be caught outside these boundaries. This means that, while crayfish are protected within the marine reserves for part of the year, they might be caught outside the reserve at other times of the year. Researchers are still adding to this evidence which indicates existing marine reserves in the Hauraki Gulf are not large enough to protect crayfish.

A proposal to extend the offshore boundary of Cape Rodney-Okakari Marine Reserve was included in the 2021 Hauraki Gulf Marine Spatial Plan. Amongst other things, this plan suggests increasing the offshore boundary of Cape Rodney-Okakari Point to 3 km from the coast, in order to mitigate the effects of fishing on the offshore (deep water) boundary. According to Dr. Benjamin Hanns, ‘while this extension will prevent further capture of current lobster populations on the offshore boundary, current fishing effort is low on the offshore boundary likely because of the low population size and consequent low catch rates.’

It takes 6-7 years for kōura to reach sexual maturity, but they can live more than 30 years. This leads to pondering if more can be done to help the crayfish populations? Unfortunately there is no simple solution, in addition to experiencing an immense amount of fishing pressure, crayfish in the Gulf have experienced several years of low recruitment which means there’s been a reduction in the number of larvae that develop into juvenile crayfish. PhD research by Dr. Hanns presumes that ‘recruitment is a major factor limiting reserve population densities, therefore extending reserve boundaries to accommodate crayfish movement is precautionary’ in the event of successful recruitment. Expansion of the reserve boundary means more crayfish moving offshore are protected and therefore recovered populations will be more likely to be resilient to subsequent fluctuations in recruitment.

Marine reserves play a significant role in providing unfished references. It’s important to see marine reserves to be ‘normal’ numbers of crayfish, what populations elsewhere could be if they had protection. Our few crayfish outside the reserves may be as little as just 3-12% of unfished levels. We then really need marine protection to act as insurance against future extractive pressures and recruitment uncertainties.

There’s a chance crayfish populations could recover in the Gulf, but not if we don’t make changes. There’s 95% more crayfish in these protected areas compared to what you can find outside of reserves in the Hauraki Gulf, so there’s no doubt that as a whole they would benefit from a bit more protection.

In fact, some communities are stepping in and taking action on a local level to protect crayfish. For example the Waiheke iwi have laid a rāhui over kōura and three other species in notable decline. In response, the government has temporarily closed the fishery for crayfish, paua, scallops and mussels around the entire Waiheke coastline, out to one nautical mile (1.8 kilometres), for a minimum period of two years. In an effort to determine the effect of this, volunteer citizen scientists are also undertaking crayfish surveys which you can find information about or learn how to get involved via the Waiheke Marine Project website.