Kawau tikitiki / spotted shag are one of our most beautiful endemic seabirds. Nationally the species is considered vulnerable with large but declining populations in the South Island. However, the situation is more dire for kawau tikitiki in the Hauraki Gulf / Tīkapa Moana / Te Moananui-ā-Toi where a small and genetically unique population is facing a grim future.

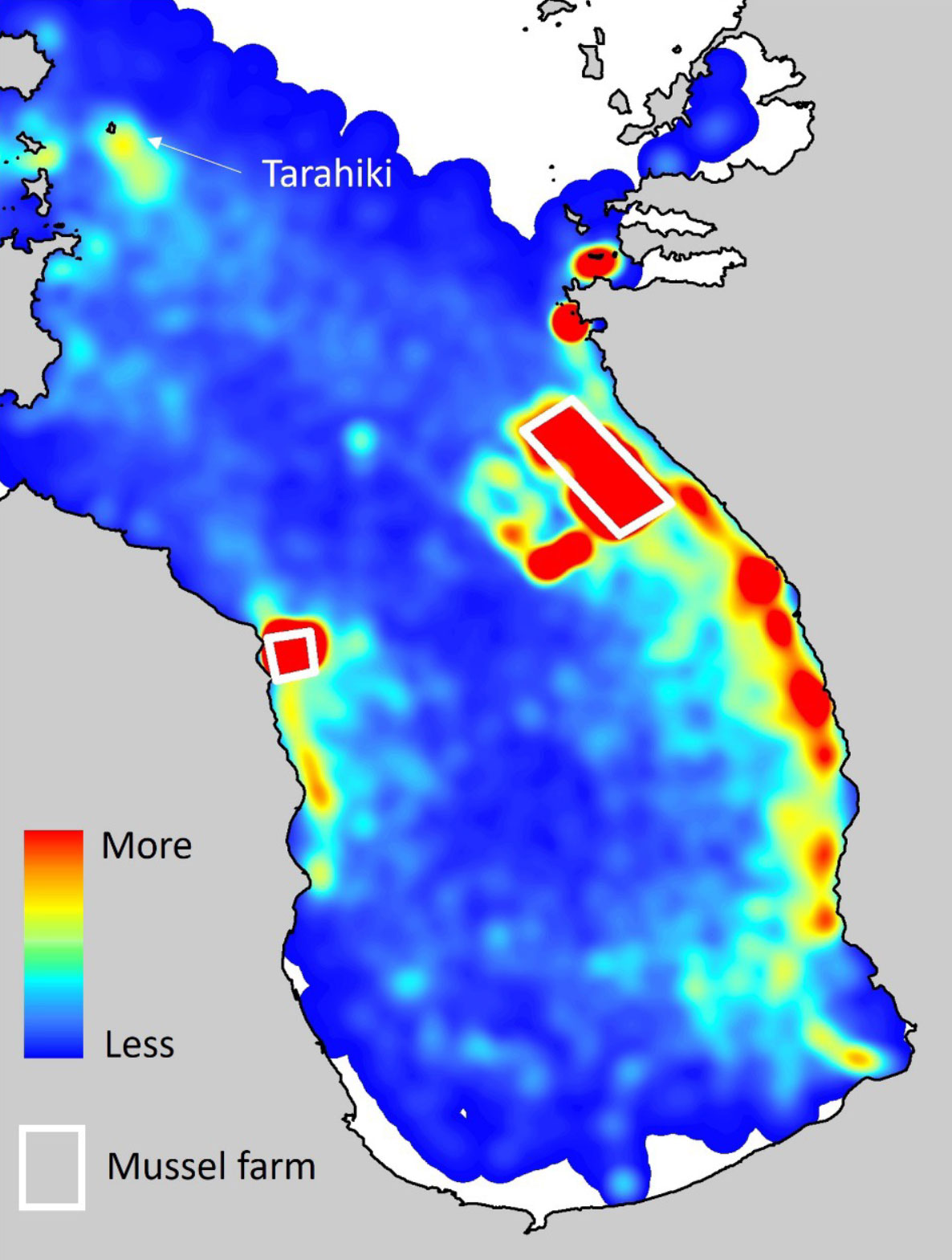

Kawau tikitiki were historically abundant in the Gulf – numbering tens of thousands – with midden deposits suggesting the species was an important source of kai for Māori. However, since the early 20th century the Gulf population has experienced declines and increases with an overall steep negative trend. While widespread before 1910, by the early 1930s the decline of kawau tikitiki colonies prompted legislation to halt their extermination by shooting, carried out in the mistaken belief it protected fish stocks. With protection, kawau tikitiki numbers increased after 1940 and by the 1960s surveys counted over 2000 pairs breeding in the species last stronghold of the Firth of Thames. However, by the 1980s colonies were again declining with the last west coast colonies in the Auckland and Waikato regions going extinct in the 1990s and early 2000s. Today only 250 breeding pairs of this beautiful cormorant are left in the Gulf with our monitoring data since 2015 suggesting a slow decline. On-land threats to the remaining kawau tikitiki colonies are limited, with the bulk of the population breeding on the safe cliffs of predator free Tarahiki Island. Of more importance are threats at sea with research indicating how these birds are part of a bigger story of the decline in the health of the Gulf ecosystem.

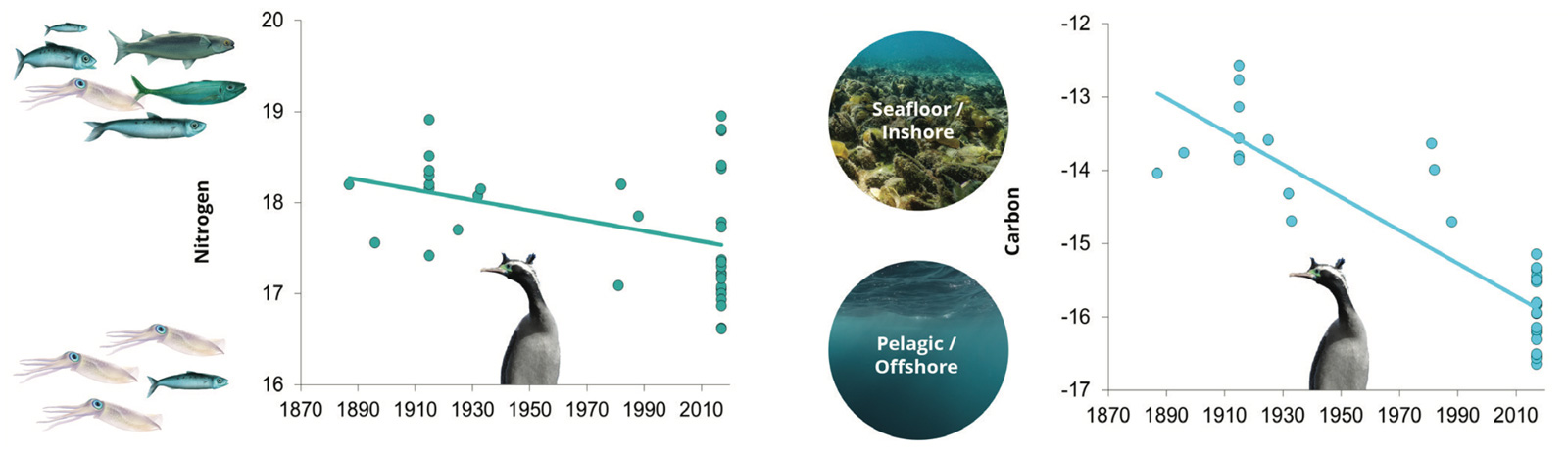

To find out what might be driving the decline of kawau tikitiki in the Gulf Auckland Museum / Tāmaki Paenga Hira conducted a study. We tracked the stable isotope values in feathers from specimens held in our collections and from wild sampled birds from 1887 to 2017 to tell us about changes in their diet and foraging habitats over time. Kawau tikitiki just love fish and pursue them underwater in dives up to 25 metres deep that can last over a minute. Nitrogen isotope results indicated the foraging trophic level of the birds has declined over the past century. This suggests that the types of food that birds eat has changed, and they are now eating things that are lower on the food chain. Where previously the birds had a diet dominated by fish, they are now eating lower tropic-level pretty like squid which are less nutrient rich.

More surprising was a carbon isotope result indicating that around the between the 1980s and early 2000s birds underwent a major change in foraging habitat – moving further offshore. This happened around the time that populations began their decline to today’s numbers.

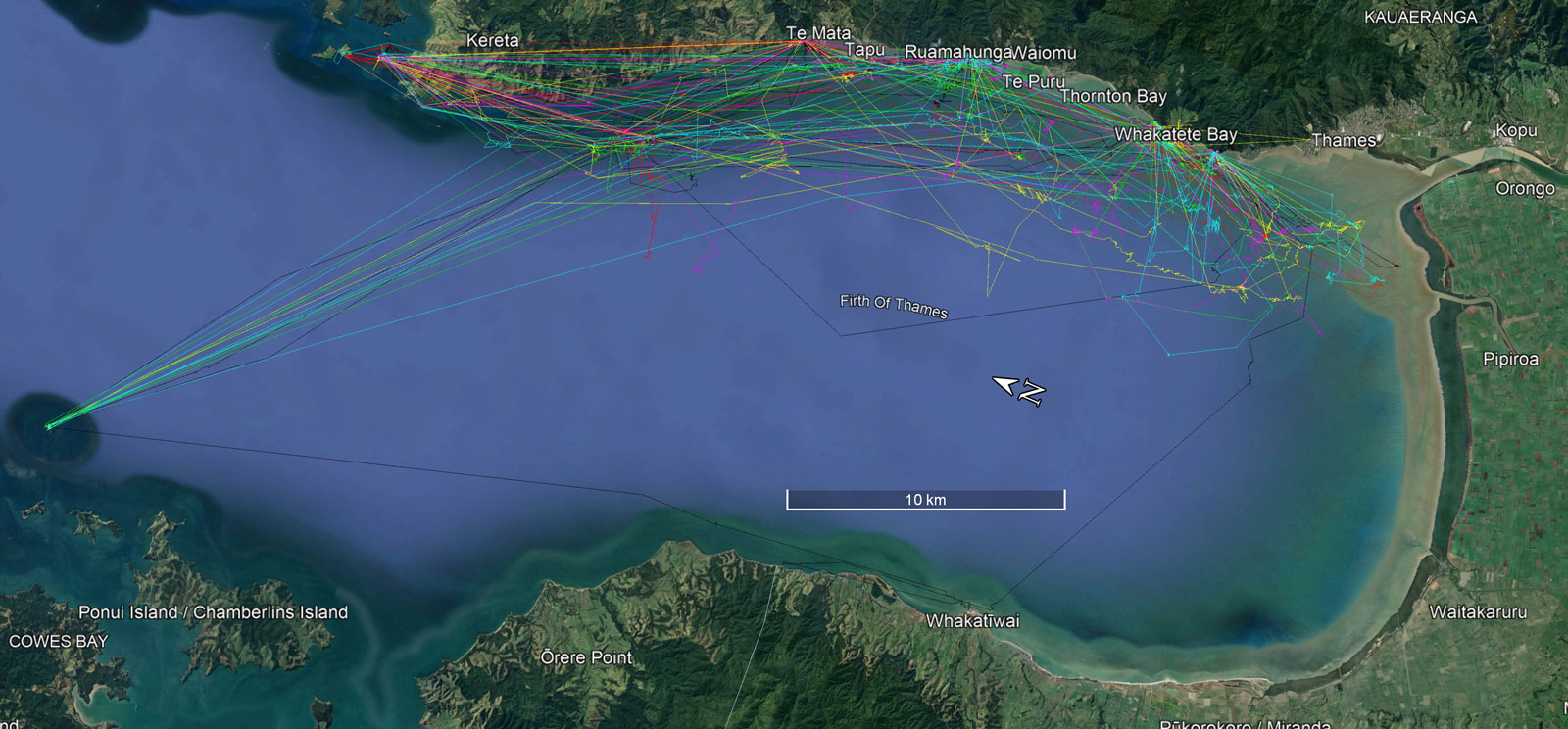

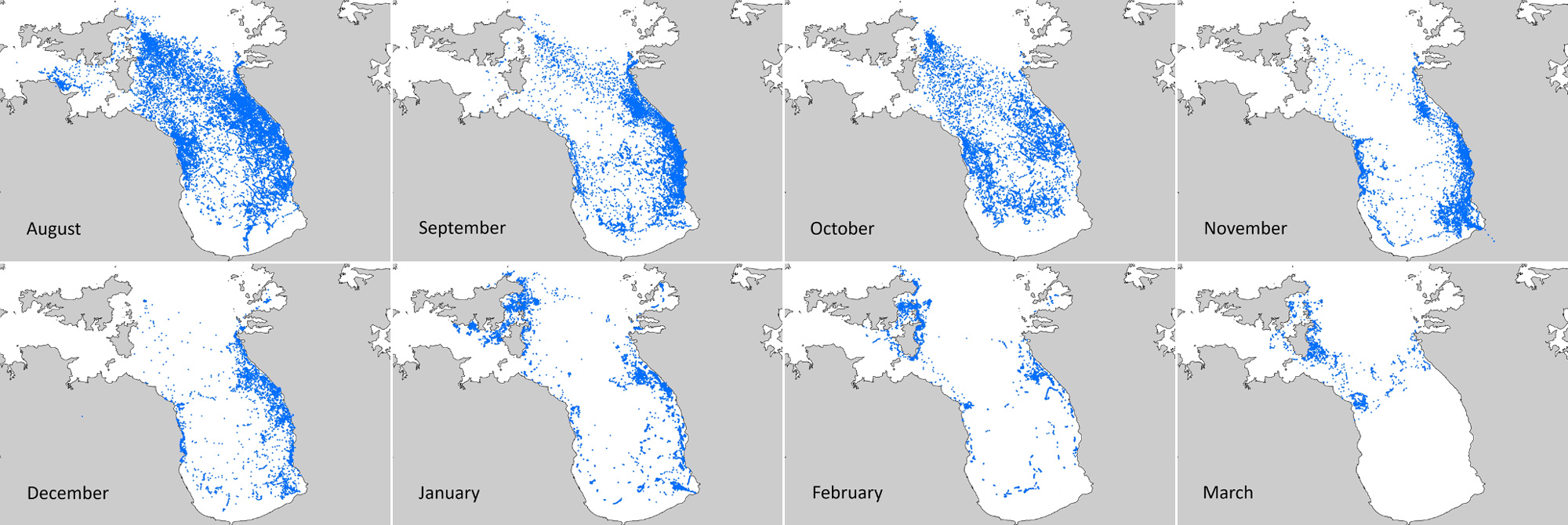

In 2020, in partnership with the Auckland Council and Orgeon State University we commenced a four-year tracking project of kawau tikitiki to find out more about their lifestyles. Birds have been caught at their breeding colonies and tagged with trackers that log the depth and GPS location for every foraging dive and upload the data through the cell phone network. Throughout the year birds make extensive use of offshore kūtai / mussel farms in the Firth of Thames potentially explaining changes in feather carbon isotope signatures.

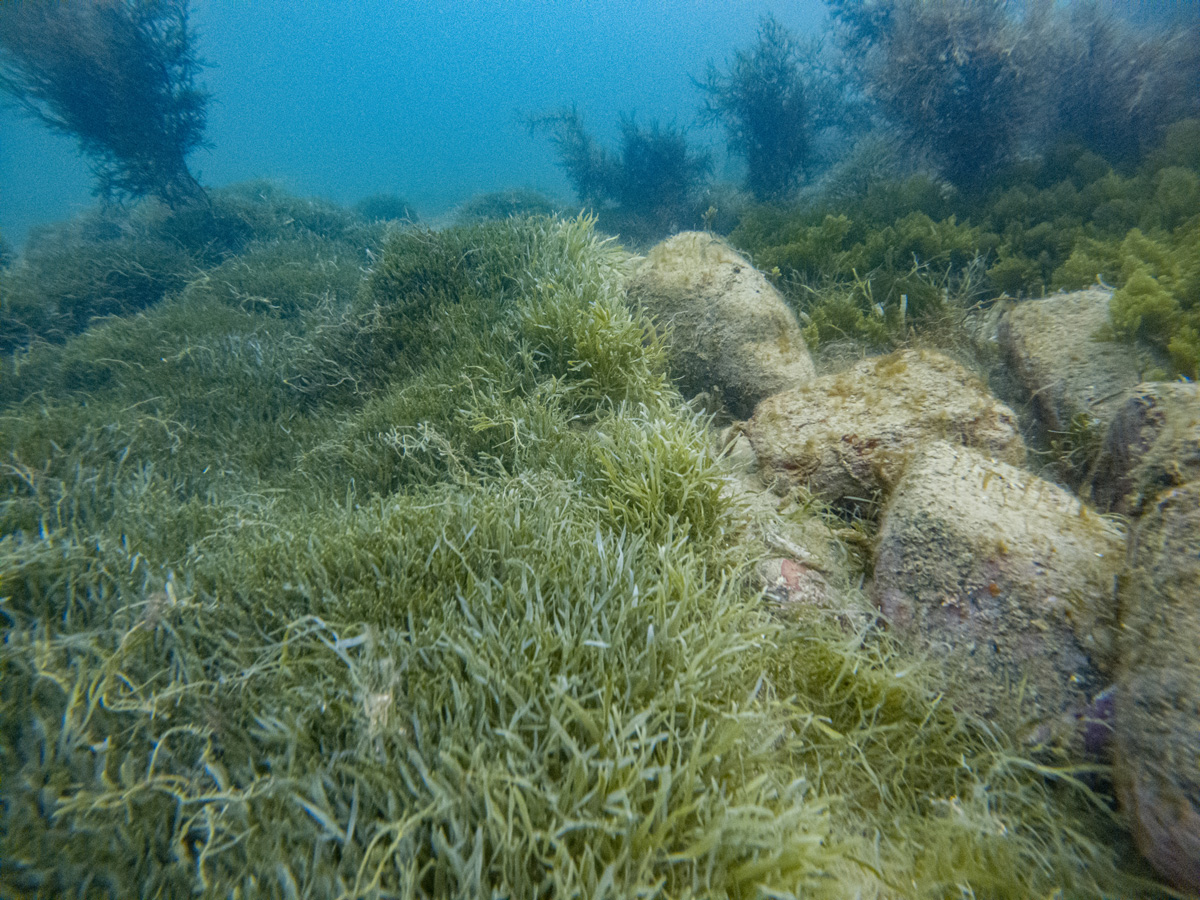

On the farms birds make shallow dives at the surface but also dive to the seafloor (15-20+ metres) where the kūtai clad lines support an rich marine community where shags can find prey. Such communities were historically found in the form of vast kūtai beds and other benthic structure across much of the Firth, and indeed wider Gulf, but have been lost to dredging and prevented from returning by vast amounts of silt and pollutants coming off the land and choking the seafloor.

Seasonally, birds exploit the Southern Firth during late spring and early summer (November – January) and particularly the mouth of the Waihou River. However in February and March birds strikingly abandoned the Southern Firth completely, moving into deep water channels surrounding the eastern end of Waiheki, Ponui, Rotoroa and Pakatoa. This shift coincides with a late summer peak increase marine productivity and reduced oxygen levels in the Southern Firth fed by vast amounts of inorganic nitrogen runoff from the Waihou and Paiko Rivers that may be impacting prey availability for kawau tikitiki and explain their departure.

Our research suggests that the destruction of kūtai beds and modification of inshore food webs have had and are continuing to have a profound impact on kawau tikitiki, forcing them to adapt and shift to deeper water foraging habitats. With only 250 pairs left uncertainty lingers over how much longer these beautiful cormorants can endure. They serve as a delicate indicator of the complex ecosystem-wide challenges our Gulf is facing. Such issues can only be addressed with ecosystem wide restoration initiatives and broad societal collaboration.

To restore kawau tikitiki populations we should increase prey availability by:

- Temporarily reducing or eliminating commercial harvest of forage fish in the Gulf

- Protecting benthic habitats by banning bottom trawling, reducing sediment pollution, and restoring mussel reefs in suitable habitats

- Reducing nitrogen and pollutant inputs which damage marine ecosystems

- Developing a network of large marine protected areas where whole ecosystems can flourish providing food for top predators such as kawau tikitiki to feed on

If we hope to preserve the presence of these magnificent cormorants in the Hauraki Gulf for generations to come, it’s crucial that we take such actions. These birds’ survival and well-being are directly linked to the choices we make today.