By Brittany Mathias and Shaun Lee. This story first appeared in Tales of the Hauraki Gulf (Auckland Writers Anthologies) Sue Glamuzina 2024.

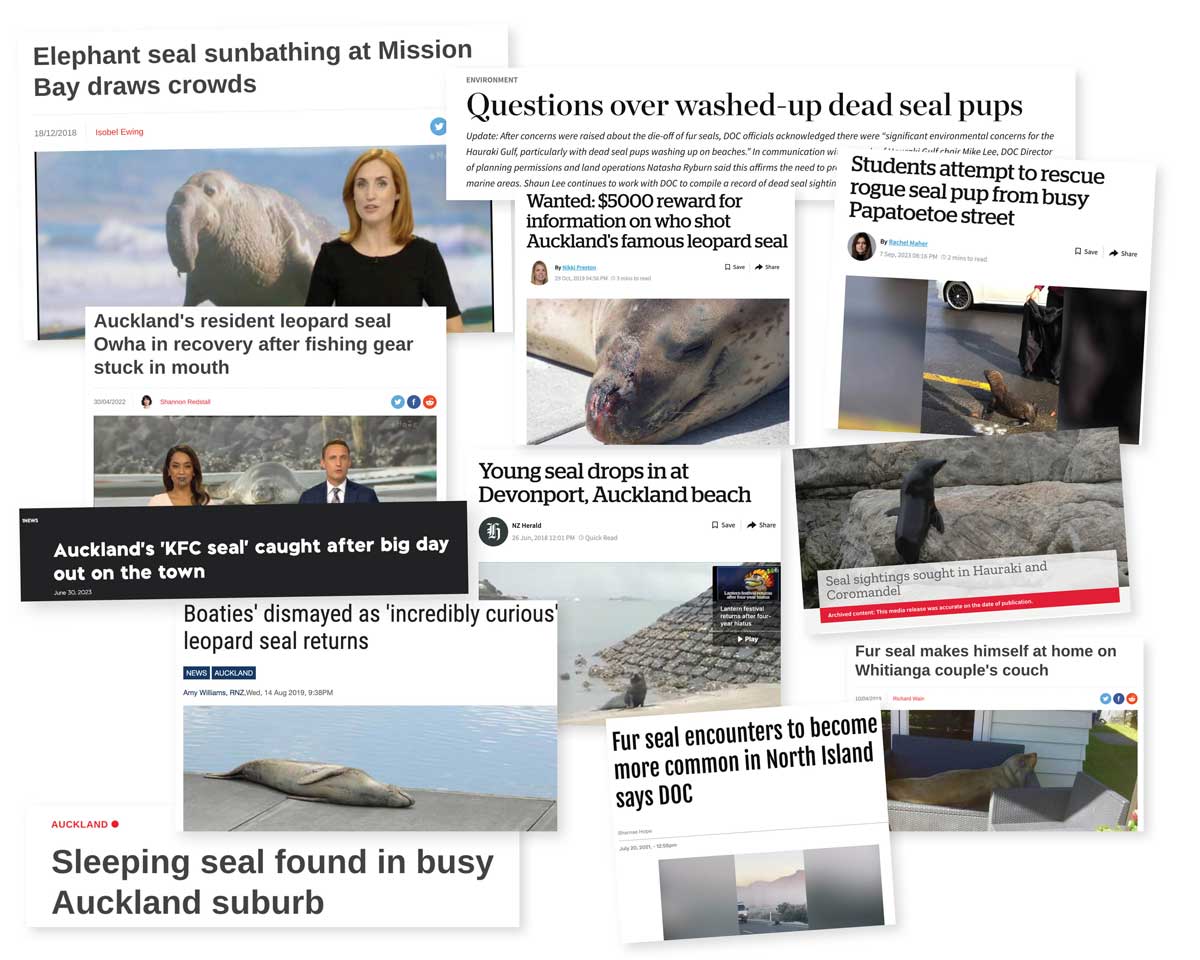

How would you react to finding a leopard seal lazing on your local marina pier or a seal pup out for a day on the town at the local KFC?

Despite the declining health of the Gulf, seals are making a comeback. After being hunted to near extinction for over a century, these marine mammals are returning. And while it’s a conservation success story, interactions with humans are becoming increasingly more common.

When humans and animals interact it often leads to conflict. This can have devastating impacts for both species. Wild animals can behave unpredictably when put under stress and may defend themselves if they feel threatened causing injury or even death to humans. In some parts of the world, tourists approaching wildlife too closely has prompted officials to euthanise individuals in order to protect public safety. For example, in 2022, “Freya”, a walrus in Norway was euthanised due to fears of potential harm to humans and inability to maintain animal welfare. Despite dozens of pleas from officials to give her space, curious onlookers continued to approach her to take photos, throw objects at her, swim with her and surround her in large numbers.

Over time animals may become accustomed to humans and may seek out human contact. Conditioned seals can become a problem as they may seek to ‘play’ with beach goers and swimmers. And then sometimes, well meaning people think an animal needs assistance, when they are actually doing more harm than good. For example, beachgoers will often try to feed seals, thinking they are sick or injured. Human food is unhealthy for wildlife, and regular access to it can cause seals to become reliant on us for their meals, causing them to no longer seek out natural food sources. People have even been recorded trying to return seals to the water thinking that the animals are stranded. For example, someone once removed a young pup from a beach on the South Island and took it on the ferry to be assessed by a vet in the North Island. Unfortunately, the seal was too young to survive without its mother and had to be put down.

Of course, not all interactions with wildlife are negative. Interactions with wildlife can improve human wellbeing and lead to increased support for wildlife conservation. As the human population expands, we continuously adapt our behaviour to live harmoniously with one another and protect wildlife. These adjustments are an ongoing effort as we learn about each other, and what’s working.

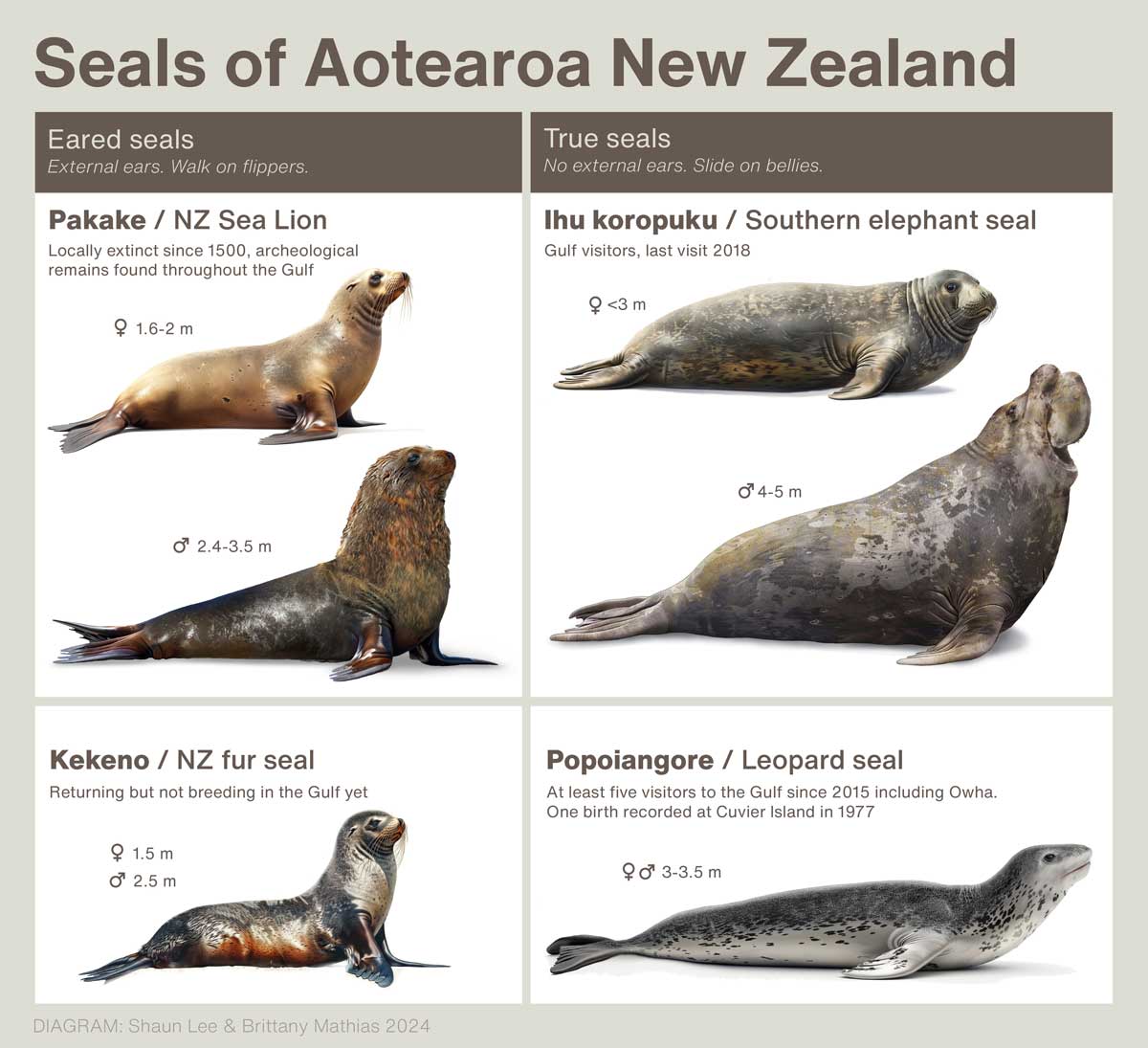

Seals and Sea lions in New Zealand

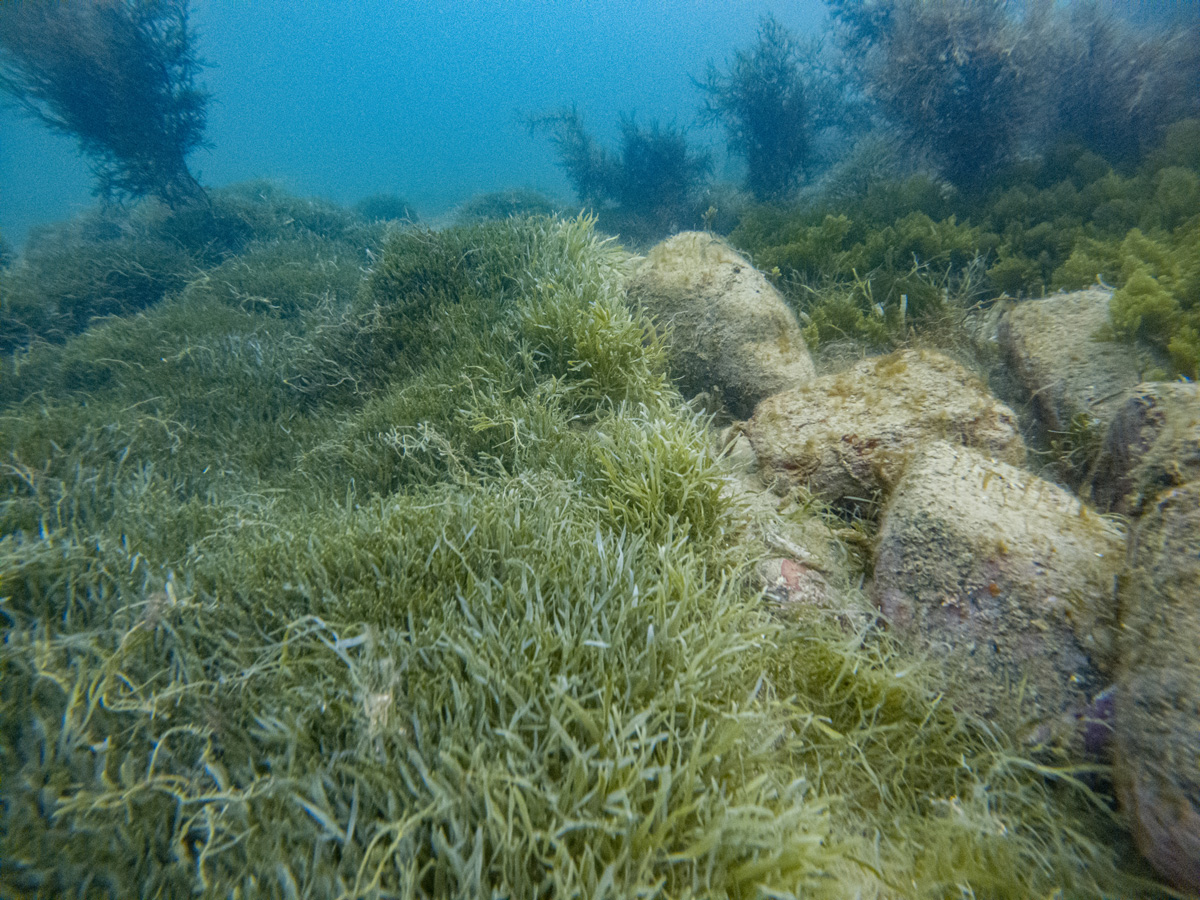

When the first Polynesians arrived in New Zealand around 800 years ago our shores would have looked very different – fur seals and sea lions would have been found throughout the coastal area. Māori would have hunted them in big numbers – living in large colonies, seals were easy to find, providing a good source for food and clothing.

As Europeans arrived in the late 18th century sealers and whalers came in the hundreds, hoping to make their fortune – catching seals for food, fur and oil. Soon seal skin hats, coats and footwear were being sold throughout Britain. Seal blubber was rendered to provide oil for lamps. Sealing would continue until 1946, decimating our seal populations to near extinction.

Seals and sea lions belong to a group of mammals known as the pinnipeds, which have limbs that are modified into flippers and streamlined bodies for efficient movement through the water. Four species of seals are regularly seen around the New Zealand coastline.

Kekeno/New Zealand fur seals

Kekeno are the most common marine mammal found on our shores, found throughout our coastline as well as western and southern Australia. The last population estimate was in 2001 which put the population at 200,000 individuals (it’s higher now, but by how much is unknown) – probably 5 to 10% of the number before humans arrived. Breeding colonies occur as far north as Moutohora Island, off Whakatane. However, there is no known breeding colony within the Gulf.

Fur seals in New Zealand follow a predictable seasonal pattern, with newly weaned yearlings dispersing from the breeding colonies from May to September. Juvenile fur seals have been found over 1000 km away from their place of birth. Tagged fur seals from Cape Foulwind on the West Coast have been recorded in the Gulf. As the newly weaned juveniles begin to explore the world (a bit like a teenager on their OE) we start to see an influx of seals on our shores, often putting them in conflict with people and dogs. There is an ongoing effort to find out why so many Kekeno are found dead on the beaches of the Gulf, regular mortality events for Kekeno in early September are dominated by pups and yearlings, more than half of them do not appear to be dying of starvation.

Although seals are marine mammals, they spend a lot of time on land – coming ashore to rest, moult and breed. On land seals have been found in unusual places such as backyards, drains and roads. They can travel quite far inland, often by following rivers or streams. The Department of Conservation (DOC) receives a huge number of calls every year from concerned members of the public who are worried that these animals are sick or injured. Sneezing, coughing and regurgitating are normal seal behaviour and shouldn’t be mistaken as a sign of distress.

DOC uses a hands off approach when it comes to wildlife and will only intervene if an animal is in immediate danger such as getting too close to a road, entangled in fisheries debris, being harassed by people/dogs or seriously injured. If we can educate ourselves on the natural behaviours of these animals then we are better placed to help seals when they really are in trouble.

Learning to live together

Seals are using the Gulf in different ways! But we still have a lot to learn about these animals! As seals continue to return to our shores, we will need to learn how to coexist. With the movement of other species into the Gulf due to climate change, pressures from humans or move into previously occupied areas due to conservation efforts, we can use the story of the Kekeno as an example.

Steps forward:

Managing human wildlife conflict requires management of both animals and people. This requires input from not only scientists and conservation managers but local communities as well.

Here are some ways we can help through policy and legislation, community outreach and awareness, and through our individual outcomes.

- To reduce conflict safe places for seals should be planned for in regional coastal management plans.

- Seals are part of an intact ecosystem, fishing methods and seal prey biomass should be considered in the Hauraki Gulf Fisheries Management Plan.

- Citizen science is an important tool for understanding how our seal populations are recovering and learning about how seals using the Gulf. Citizen science promotes collaboration between conservation managers, researchers and members of the public. Sightings of seals within the Gulf can be reported on iNaturalist.nz

- Local communities around the Gulf need to take ownership of their backyard and be kaitaki/guardians of the places they visit. This could mean educating yourself on how to watch wildlife responsibly, learning more about the Gulfs seals, keeping your dogs on a leash when out for a walk or picking up rubbish at your local beach.

If you encounter a seal while enjoying the Gulf, enjoy the experience – remember how lucky we are to live alongside these beautiful animals.