Last year when New Zealand entered its first COVID-19 lockdown, there were many interesting environmental observations made such as increases in the number of birds visiting our gardens or dolphins and seabirds seeming closer to shore during our daily exercise to the local beach. Whether this was due to the wildlife responding to the decrease in human activity or whether we simply had the time to take notice of what was around us, it isn’t always easy to draw a clear conclusion.

However, for researchers at the University of Victoria (British Columbia) and the University of Auckland, lockdown provided the opportunity to record an unplanned set of data. In the months prior to lockdown, Matt Pine and his team had been deploying hydrophones around the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park to collect data for their Department of Conservation Hauraki Gulf Cetacean Fund research.

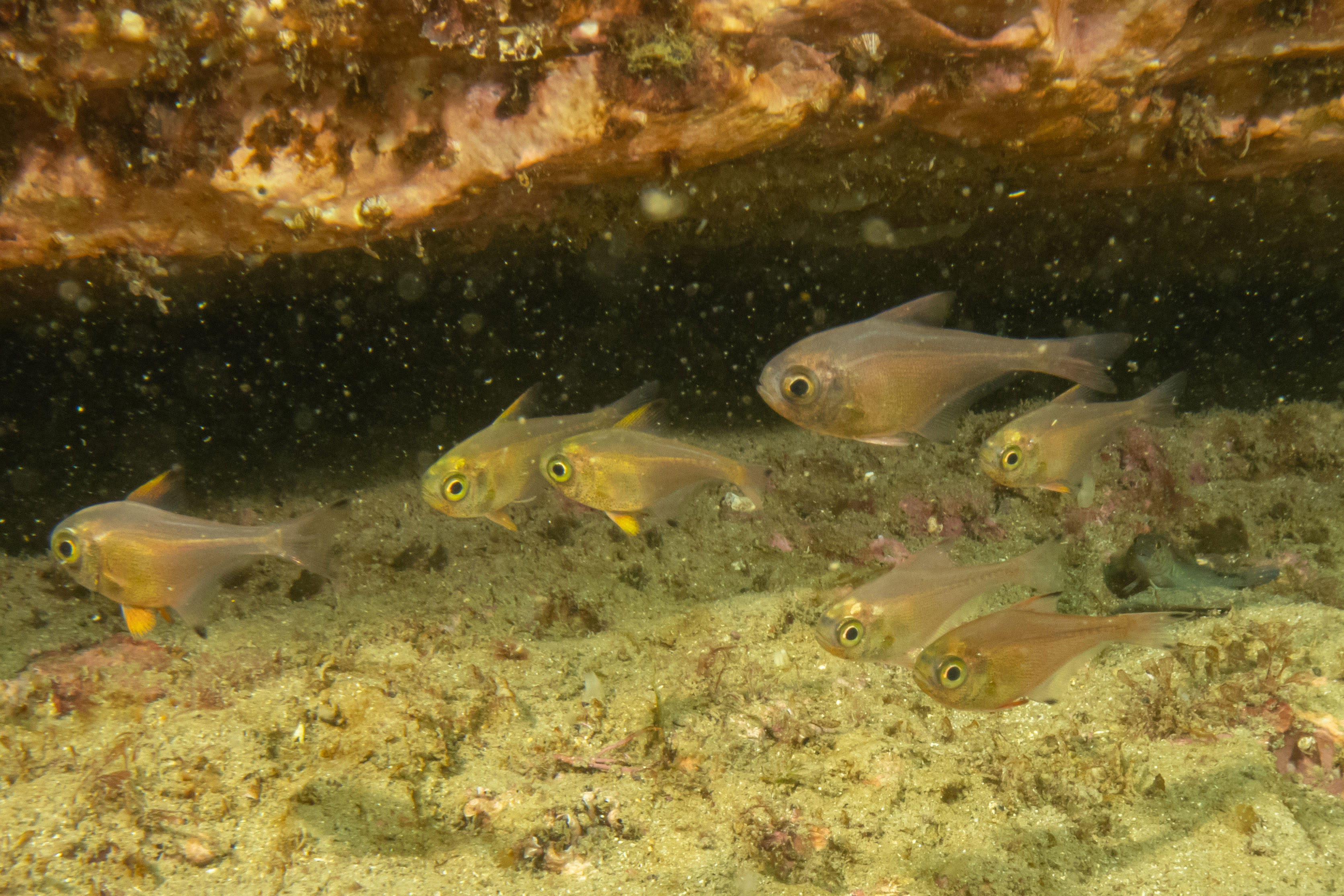

The hydrophones were being used to measure the impact of tourism and small recreational vessels on the Marine Park’s marine wildlife, building upon prior acoustic and behavioural studies such as Putland’s study on the impact of shipping vessel traffic on the communication space available for wildlife. Results in Putland’s study had found that communication space for the resident Bryde’s whales reduced by up to 87.4% and by 61.5% for New Zealand bigeyes when in the presence of these large vessels.

With the hydrophones deployed and New Zealand suddenly under lockdown, a set of clear acoustic data of the marine life that came close to the hydrophones in the absence of marine traffic could be recorded. The results showed that there was an increase in communication ranges for fish and dolphins by up to 65%. At a hydrophone stationed close to Auckland City, the range of communication increase by 50m for every 10% decrease in vessel activity for dolphins and 18m for fish. Further away from the city, this range increased to 510m and 13m respectively.

Besides the current global pandemic there are not many examples of where a drop, as opposed to an increase in marine traffic, has provided the opportunity to reveal the impacts of human activity. Possibly one of the most well-known instances in the marine mammal community is that of the disaster of 9/11. Researchers studying the migratory North Atlantic right whales in Canada’s Bay of Fundy analysed faecal samples for levels of the stress-related hormones, glucocorticoids and compared this with samples they took in subsequent years. Results showing a drop in glucocorticoids and then a gradual increase post 9/11 which was attributed to the sudden ceasing and then resumption of maritime traffic and therefore acoustic noise in the wake of the disaster.

Impacts of our increasing levels of daily activities that we undertake are being conducted worldwide but it is not always common to be able to obtain data where activities nearly stop. The 2020 lockdown allowed researchers to gain a rare set of data for the Marine Park which, along with other data collected outside of the lockdown period, will help us understand how human activities are impacting the marine wildlife and subsequently inform how the area could be managed going forward.