Summary:

A major argument against the proposed increase in marine protection in the Hauraki Gulf is that it will simply increase pressure and drive fish stocks down in the surrounding areas. Available data and published literature provides strong evidence that these concerns regarding “displaced fishing effort” are likely overstated:

- Only 9% of the recreational catch and 6% of the commercial catch for tāmure/snapper taken from the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park occurs within the proposed High Protection Areas (HPAs).

- Recreational and commercial fishing effort is constantly shifting across the Gulf at spatial scales greater than the proposed HPAs.

- Most recreational and commercial fishing catch consists of highly mobile transient tāmure/snapper rather than reef-associated resident tāmure/snapper, the latter of which are at very low levels.

- The proposed HPAs are expected to increase tāmure/snapper biomass and egg production of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park by 380% and 350% respectively.

- The positive impacts to snapper and wider biodiversity from protection in the proposed HPAs will outweigh any potential negative impacts.

- In short, there will be more fish, and better fishing.

Dr Benn Hanns

On the 9th of August last year, then Prime Minister Chris Hipkins announced that the Hauraki Gulf / Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Bill would be introduced into Parliament. The proposal includes extensions of two marine reserves, the establishment of 12 high protection areas (HPAs) that will only allow restricted harvest for customary practice, and five seafloor protection areas. This represents an unprecedented step towards meaningful protection for the Hauraki Gulf. This bill is the culmination of a decade of planning, including stake-holder consultation followed with a review by an independent Ministerial Advisory Committee. While the public’s response has generally been positive, there is after all overwhelming support for more marine protection in New Zealand1,2, opposition has emerged on both social and mainstream media3. The main argument against the proposal is summarised by the recreational fishing lobby group LegaSea’s stance, that “Marine protection and fisheries management controls need to go hand-in-hand, otherwise all we will do is shift current fishing effort into our neighbour’s waters” 4.

The concern is that recreational and commercial fishing currently occurring within the 12 proposed HPAs will be shifted or displaced from these areas into neighbouring areas. This argument of “displaced fishing effort” assumes that by completely closing areas to fishing, fishing pressure will simply increase in surrounding areas and accelerate environmental degradation in those areas. In theory, this makes some sense, and it is understandable why this ‘concern’ has gained traction among those that like to go fishing or whose livelihoods depend on it. However, this argument is also based on big assumptions regarding fishing behaviour and the ecology of targeted species. It is therefore unclear how big this problem may actually be. To better understand how displaced fishing effort may impact the Hauraki Gulf and to determine whether this concern has merit, it is essential all available information is first evaluated. This includes reviewing the relevant international scientific literature, assessing spatial patterns in the commercial and recreational fisheries, relating this to the ecology of targeted species, and evaluating whether advantages of increased protection outweigh perceived negative impacts.

Is there evidence for displacement effects?

Displacement arguments against marine protected areas (MPAs) are almost as old as MPAs. Despite this, countless MPAs have been established globally, and in many cases, these have been well-researched scientifically for ecological changes. If displacement is an issue of such pertinence, then it would be assumed that the scientific literature must be overflowing with supporting evidence. But it is not. In a global review of published literature undertaken by recent University of Auckland Master of Science graduate Rebekah van Dort, it was found that only 12% of the studies reported negative impacts arising from displaced fishing effort. Of these, the majority were simulation or modelling studies (i.e. theoretical), with only a few showing actual empirical evidence (i.e. real data) for negative displacement effects.

So why is there so little supporting evidence? At its core, the displacement argument is based on the logic that the same fishing effort will simply be redistributed over the adjacent areas. However, we all know that fisheries and fishing effort are highly flexible, and effort is constantly shifting from one place to another based on factors completely unrelated to marine protection. These include weather, fuel costs, targeted species, and trends in fishing equipment. Another fact that is also largely ignored is that many key fisheries target highly mobile and transient species. While positive conservation effects within MPAs are known to transcend their boundaries and MPAs have been shown to influence neighboring fished areas through the movement or spill-over of adults and the transfer of larvae or recruits. This is not considered when displacement arguments are made, instead they assume that fish, and by extension their offspring, are locked away in perpetuity.

How much fishing occurs in the proposed HPAs?

Thanks to aerial survey and commercial fishing position reporting data provided by the Ministry of Primary Industries, we have a good idea of where recreational and commercial fishing activity occurs and how much tāmure/snapper in particular are caught. Using the most recently available data5,6, 9% of recreational tāmure catch and 11.5% of recreational fishing events targeting tāmure in the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park were found to be occurring within the proposed HPAs. Likewise, only 6% of commercial catch and 7% associated fishing events for tāmure occurred within these areas. If this catch or fishing effort was simply displaced over the surrounding area evenly, this would only equate to a relatively small increase in fishing pressure in the neighboring areas. Alternatively, an increase of this magnitude, spread across the wider Hauraki Gulf Marine Park is unlikely to have an impact on the overall marine ecosystem, even if fishing pressure is not even and some localised areas have higher fishing pressure.

Fishers are individuals too!

The disparity between catch and fishing effort (sum of fishing events within area) provides evidence that not all fishing events equate to the same levels of catch. For all recreational fishing occurring across the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park, 25% of the total tāmure catch can be associated with just 4% of recreational fishing events. While 40% of the commercial tāmure catch was taken by only 15% of commercial fishing events. This shows that it is incorrect to assume that all fishing effort displaced will have the same impact. Not all fishing is equal. Recreational fishers are motivated by different reasons, such as to catch fish for food or sport, while others may focus on enjoying the time on the water and take a more casual approach to fishing. Although commercial fishers are generally united by the common goal of having a sustainable fishery while maximising profit, landings are still expected to greatly vary between vessels due to different vessel sizes, quota allotments, and fishing methods used. For example, over the 2020 fishing year precision bottom trawling represented 10.8% of all commercial fishing events for tāmure in the marine park but contributed 20% of total catch. In contrast, baited long lining represented 49% of commercial fishing events and 47% of total landings.

Fishers follow the fish – spatial variation in catch/effort

Regardless of objective or fishing method, high catch rates at any location are not guaranteed throughout the year. A species’ ‘catchability’ (how easy it is to catch), will shift seasonally due to biological processes such as mating and spawning. In mobile species, changes in catchability can be localised and reflect population level movements from one area to another. To continue catching fish, fishers will follow the fish. From month to month, recreational and commercial tāmure fishing effort is constantly shifting at spatial scales greater than the proposed HPAs (see animation). The estimated tāmure catch (kg) in each of the HPAs showed little to no consistency from month to month, with, fishing targeting tāmure varying through space or time. Any displacement in effort resulting from the HPA implementations is unlikely to be at scales exceeding the monthly movements already occurring within the commercial and recreational fisheries.

One fish, two behaviours: resident or transient

Independent of the behaviours of fishers, tāmure/snapper are an incredibly charismatic species, possessing a varied and intricate ecology. In the Hauraki Gulf tāmure exhibits two main behaviours: fish are either resident year-round on inshore reefs or transient, undertaking large seasonal movements on and offshore. The seasonal influx of transient tāmure into the Hauraki Gulf in summer is largely what supports the recreational fishery as most resident reef-associated populations are now severely depleted. It has been estimated that between 70% and 96% of legal-sized transient fish that move into shallow waters during summer are killed by this fishing5. In contrast, recovery of tāmure within Hauraki Gulf marine reserves has generally been attributed to increases in reef associated ‘resident’ populations, as some of these fish are likely to become resident and remain within the bounds on an MPA. Although transient fish may become temporarily protected within the HPAs during inshore movements into protected areas, they will be available to the fishery again when they undertake seasonal movements back offshore. This is supported by the large seasonal variation that occurs in tāmure numbers in existing marine reserves in the Hauraki Gulf and the seasonal movements of fishers discussed above.

Based on the aerial survey and commercial fishing position reporting data, 87.5% of recreational fishing effort and 97% of commercial fishing effort was found to be taking place over soft sediment seafloor habitat (e.g. sand or mud, not rocky reef). This suggests both fisheries are primarily supported by the transient tāmure population, rather than the reef associated resident fish. While large tāmure on reefs may occasionally get caught or speared, these large reef-associated fish are incredibly rare on fished reefs in the Hauraki Gulf due to a long history of overfishing. This is clear from comparisons between fished reefs and reefs in existing marine reserves in the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park (HGMP) where large fish are more common. Past research on tāmure in marine reserves provides strong evidence that the proposed HPAs will not lock all tāmure away indefinitely. Rather, the expected recovery of tāmure within the HPAs will likely boost the overall larval and fish stock of the wider Hauraki Gulf population supporting the wider fishery. These findings highlight that fishing effort displaced out of the HPAs is unlikely to negatively impact the larger tāmure population or diminish local populations as both are mostly targeting highly mobile transient fish.

How will the proposed HPAs benefit snapper and crayfish populations?

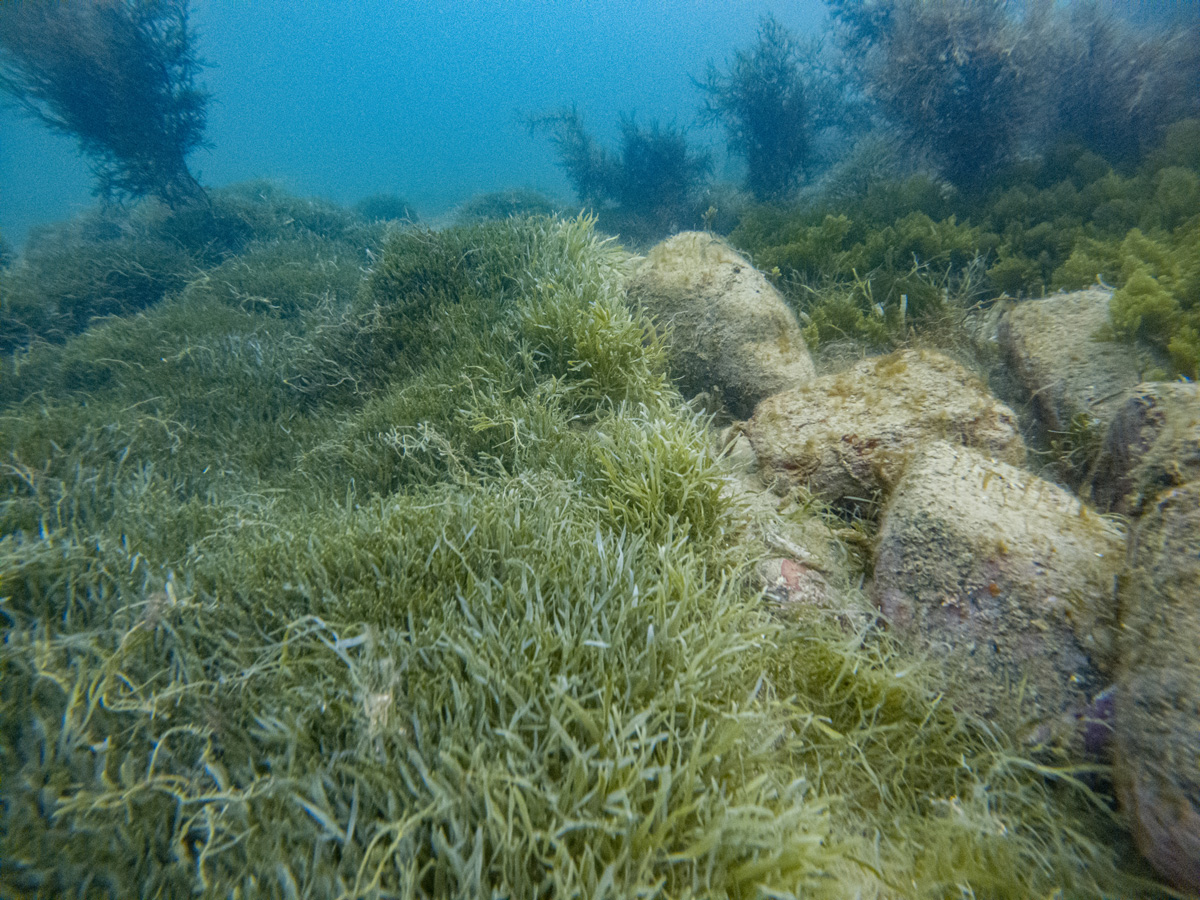

The Hauraki Gulf has a long history of marine protection. The Cape Rodney to Okarari Point/Goat Island Marine Reserve was established in 1977 and was one of the world’s first fully protected ‘no-take’ marine reserves. Since then, only 5 more fully protected marine reserves have been established in the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park, amounting to just 0.3% of its 14000 km2 area. Despite this, these marine reserves have contributed inordinately to our understanding of the impacts of fishing and the value of protected areas for rebuilding populations of important target species and restoring marine ecosystems. In older reserves, long term protection has led to the recovery of large reef predators such as tāmure and kōura/crayfish. Increased predator abundances have subsequently suppressed kina/sea urchin populations and reduced associated urchin barrens, allowing for the re-establishment of expansive and important kelp-forest habitat.

These marine reserves have also been shown to be disproportionately contributing to tāmure populations in the surrounding area. The Cape Rodney to Okarari Point Marine Reserve, despite a small size of just ~5 km2, was estimated to contribute up to 11% of newly settled juvenile tāmure to the surrounding 400 km2. If passed, this bill will increase the area of highly protected MPAs in the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park to 6%. This is a sizeable increase in rocky reef protected in the gulf, from 2.9% to 16.3%, and includes protection of key offshore island areas, which are currently unprotected. Given the extraordinary impact our existing marine reserves have had relative to their small sizes, it is easy to imagine the positive impacts of a network of this scale will have. The proposed HPAs have been designed to protect valuable ecosystems using key principles on size and configuration to ensure they are effective at protecting exploited species against the impact of fishing on their boundaries. Using knowledge gained from existing marine reserves, potential benefits to the wider tāmure and kōura populations in the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park can also be calculated. Based on known relationships between individual size and egg-production and the area of existing and proposed MPAs, estimates of overall biomass and egg production in the Gulf were generated under current levels of protection (0.3% of the marine park) and for the proposed HPAs (6% of the marine park). For reef-associated tāmure in the HGMP, biomass is estimated to increase by 3.5 times and overall egg production to increase by 3.8 times following the implementation of the HPAs. For kōura, the spawning biomass is expected to increase by 3.8 times and annual egg production to increase by 3.3 times. This preliminary analysis provides important insight into the overall magnitude of value the new HPAs can have for these important species and fisheries. This is further supported by preliminary larval dispersal modelling which follows the movement of larval tāmure hatched within the proposed HPAs and established marine reserves (see animation below).

It is not all about snapper and crayfish!

The displacement argument is a fisheries centric view of marine protection, that largely stems from concerns fishers will lose their favourite spots to fish. Although LegaSea is correct, “Marine protection and fisheries management controls [do] need to go hand-in-hand”, marine protection is about much more than fisheries. The proposed HPAs aim to protect and enhance the whole ecosystem from fishing. This includes maintaining and restoring the exceptionally complex networks of ecological interactions that form an ecosystem. Fisheries targets alone are not designed to do this. Rather, they are set to maximize productivity and to maintain the ongoing viability of a single harvested fish stock. These targets are not the same as those needed to maintain the important role that each harvested species plays in an ecosystem. The widespread deforestation of kelp forests and proliferation of kina barrens due to poor management of kina predators is a perfect example of this.

However, the need to manage the ecosystem effects of fishing are increasingly being recognised at higher levels of government. A recent High Court case ruled that Fisheries NZ is required to consider the wider ecological impacts of fishing kōura when setting total allowable catch limits. The High Court ordered a review of kōura catch limits in the Northland (CRA1) fishery due to the Minister not being provided with adequate information on incidental effects of fishing, such as those on kina and kelp6. Managing these long-standing impacts now poses a major challenge to fisheries managers as it is unlikely this can be achieved through traditional fisheries management approaches. But, it is known that these effects can be managed or reversed through effective long-term marine protection in the Hauraki Gulf.

The recent State of the Gulf report identified that 8 of the 10 fish species assessed against fishery targets are currently fluctuating around target levels (30 – 60% of unfished levels) compared to 4 out 10 in 2020. Although this indicates some improvement, the report also shows that we don’t know the status of 7 of the top 20 fished species in the gulf. This highlights the paucity of information available for the many species being caught across the Gulf and the need for holistic fishery management strategies to manage whole ecosystems. It is simply not feasible to manage an ecosystem on a species-by-species basis. With Auckland’s population growing, there are more people fishing, more fishing methods being used, and an increasing diversity of marine organisms are appearing on the menu. Reports of exceedingly high catches of unregulated species such as pink maomao7 prove fisheries management is struggling to keep up with these changes. Marine protected areas are a simple solution that at least provides some areas where our valuable marine ecosystems and all our marine taonga are protected, just as they are in our reserves on the land. This means all marine species within these areas will be protected from future changes in fishing behaviours and intensity, rather than relying on the lagging process of drafting new rules and restrictions to manage these species.

It might not quite be the Sea Change we needed, but it is a start.

Despite falling short of the internationally agreed goal of 30% protection, the Hauraki Gulf / Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Bill represents an important step towards safeguarding our precious marine environment. While it is understandable concerns about the displacement of fishing effort have been raised, our examination of available data and published literature provides strong evidence these concerns are overstated and will be outweighed by local increases in biomass and egg-production. The dynamic nature of fishing activity within the Hauraki Gulf, the mobility of targeted species such as tāmure, and the potential for spill-over effects from the HPAs all contribute to a more complex picture than the displacement argument suggests. The track record of the existing marine reserves in the Hauraki Gulf, despite their relatively small size, underscores the potential for the proposed HPAs to make a substantial difference in protecting all species while also supporting continued fishing throughout the Gulf. While the concerns of some fishing communities are valid and should be considered, the evidence suggests that the benefits of these HPAs will dramatically outweigh any potential drawbacks. It is essential that we prioritise the long-term health of the Hauraki Gulf. The establishment of well-designed marine protected areas can ensure that the vitality of this unique marine ecosystem is preserved for future generations to enjoy.

Links

1: https://www.wwfca.org/?200414/Kiwis-want-over-a-third-of-New-Zealand-oceans-protected

4: http://blog.shaunlee.co.nz/legaseas-displacement-argument/

6: https://legislation.govt.nz/regulation/public/2017/0154/latest/whole.html