Record-Breaking Year

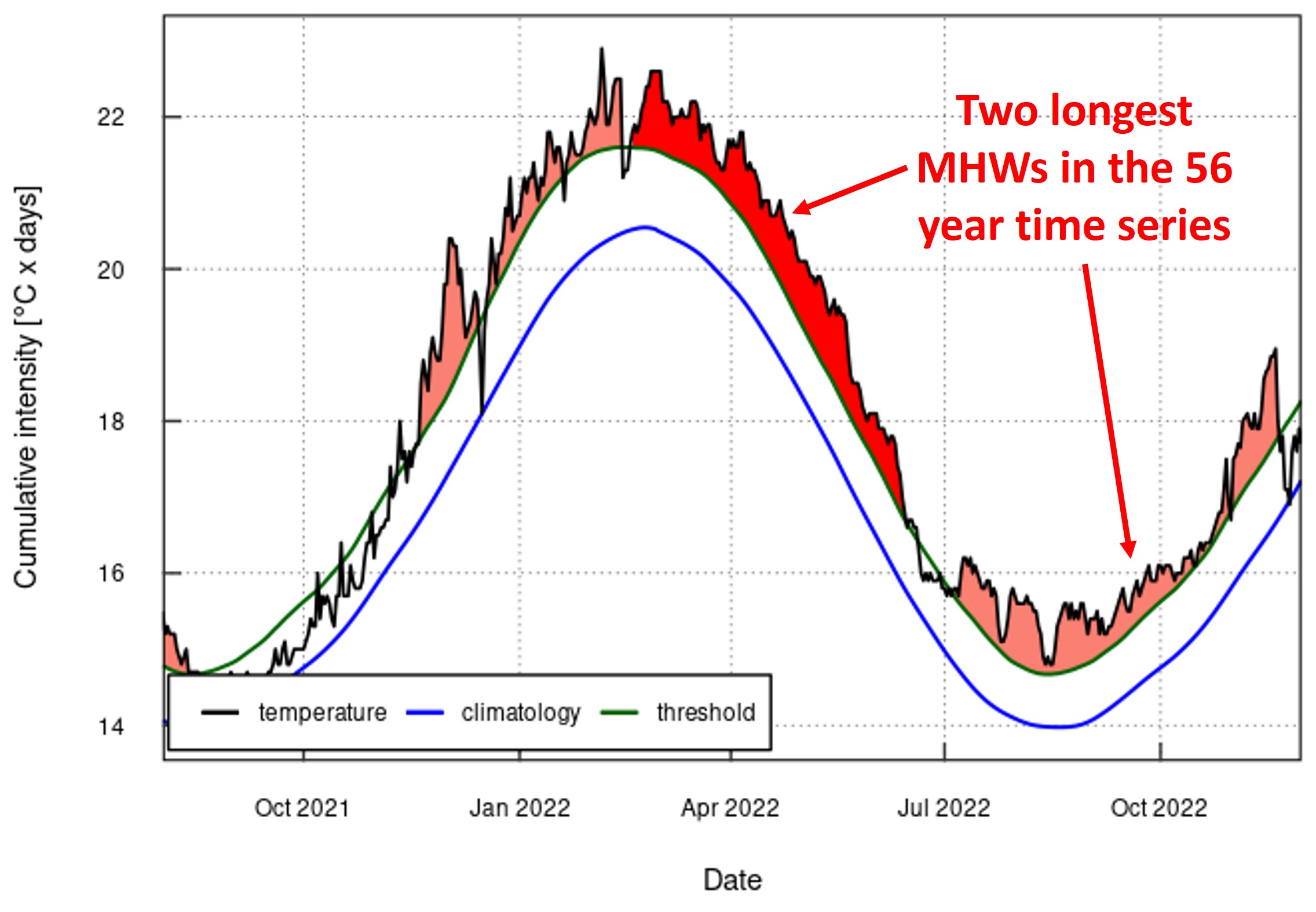

Over the course of 2022 the Hauraki Gulf, Tīkapa Moana Te Moananui-ā-Toi, has experienced prolonged periods of warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures – much longer than ever recorded. These marine heatwave conditions are defined as when seawater temperatures are greater than the 90th percentile of the historical average for more than 5 consecutive days.

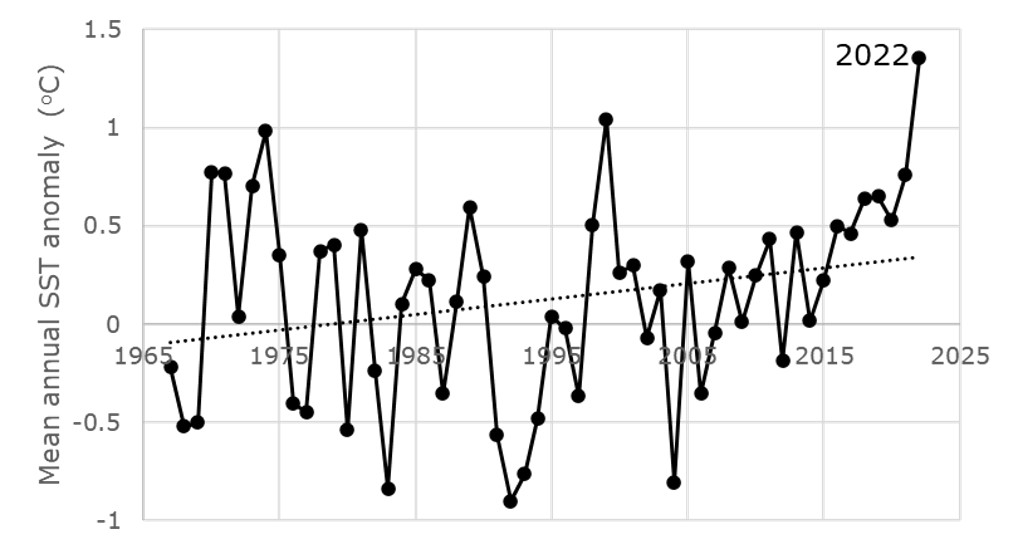

NIWA reports that nationwide, the average ocean temperature is now 1.5°C higher than it was 100 years ago, and in the past 30 years, the frequency of marine heatwave events has doubled. However, the extent of warming each area experiences varies and so localised and long-term data from the Leigh Marine Laboratory gives us a better indication of what’s going on here in the Gulf.

The University of Auckland has been taking daily sea surface temperature measurements in New Zealand’s oldest marine reserve at Te Hāwere-a-Maki – Goat Island since 1967. This makes it one of the longest coastal temperature records in the southern hemisphere and provides a unique and long-term perspective on how water temperatures are changing in the Hauraki Gulf, Tikapa Moana. Based on this long-term data set, 2022 has been the warmest year in the 56-year record – by quite some margin!

Dr. Nick Shears, from the University of Auckland, looks after the collection of long-term daily temperature records at Goat Island and is sharing with us the most up-to-date data and analysis, which reveals a dramatic upward trend over recent years.

Longer and warmer

The long-term data unveils that 2022 was a record-breaking year on many levels. The mean temperature at Goat Island in 2022 is looking to be about 0.3oC higher than the previous warmest year, which was 1999. We have also seen record-high temperatures for six months of the year (March, April, May, July, August and September). In general, we are observing the greatest rates of long-term warming over the autumn-winter period (April-July).

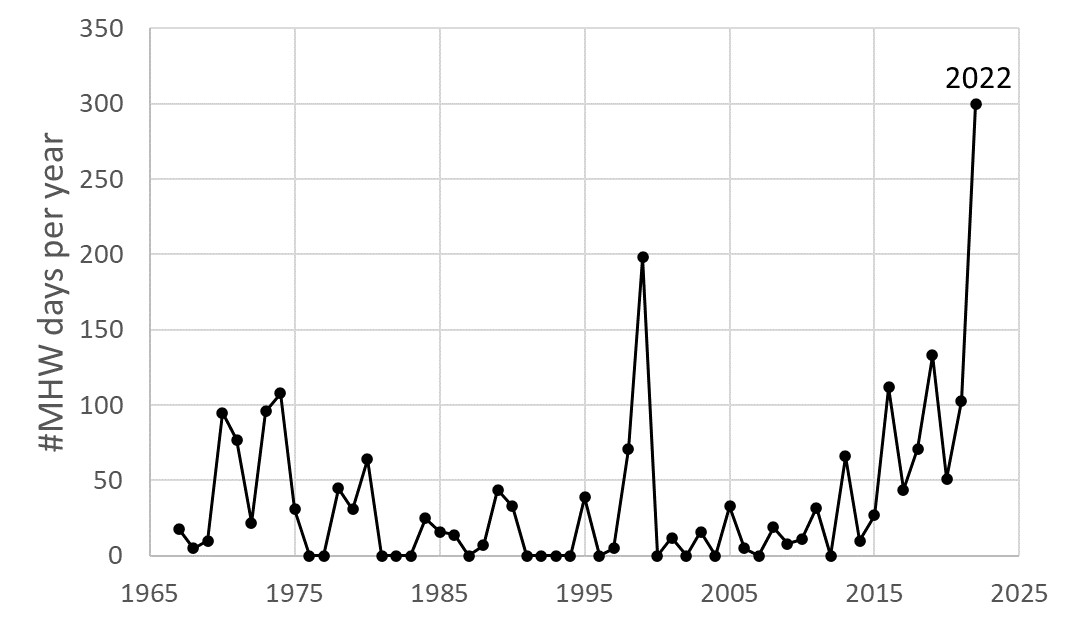

Water temperatures at Goat Island were in near continuous marine heatwave conditions from November 2021 to November 2022. Over this period, 339 days were classified as marine heatwaves, including the two longest marine heatwaves ever recorded, a total of 117 and 137 consecutive days. Prior to that, the longest marine heatwave in the Gulf was in 2016, and it lasted 65 days.

In total, there have been 300 marine heatwave days in 2022 – another record.

Ecological Impacts of Marine Heatwaves

Dive survey records provide examples of the impact these periods of prolonged warm waters are having on marine life. Earlier this year Dr. Shears and his research team documented large deteriorating sponges that appear to be ‘melting’ and becoming detached from the rocks in several locations in the Gulf.

Further to that, are increases in non-indigenous and warm water species which include the benthic dinoflagellate (Ostreopsis siamensis), the invasive tropical sea-squirt (ascidian Symplegma brakenhielmi), and filamentous algae blooms. We are also seeing longer-term increases in subtropical species such as the long-spined urchin (Centrostephanus rodgersii).

-Nick Shears

Unprecedented warming and subsequent cumulative ecological impacts are predicted to continue through this summer resulting in added stress to the Hauraki Gulf rocky reef ecosystems which are already under pressure.

Collecting the evidence

Recording the impact of marine heatwaves is important since our understanding to date of how these prolonged warm temperatures will affect marine life is limited. The impacts on the Gulf are fairly unpredictable but long-term datasets and observations are critical to helping scientists understand the impacts moving forward.

The only silver lining we can find is that marine heatwave conditions are likely to increase sightings of manta rays in the Gulf. You can report and share interesting observations with these research groups:

- Share manta sightings with Manta Watch Aotearoa New Zealand

- Report subtropical fish and invertebrates in NZ to What’s that Fish

- Record sightings of marine species & share with others on iNaturalist