The grounding of a commercial fishing vessel in the Hauraki Gulf featured a rapid emergency response. A follow up dive survey features another crisis aided by glacial political inaction.

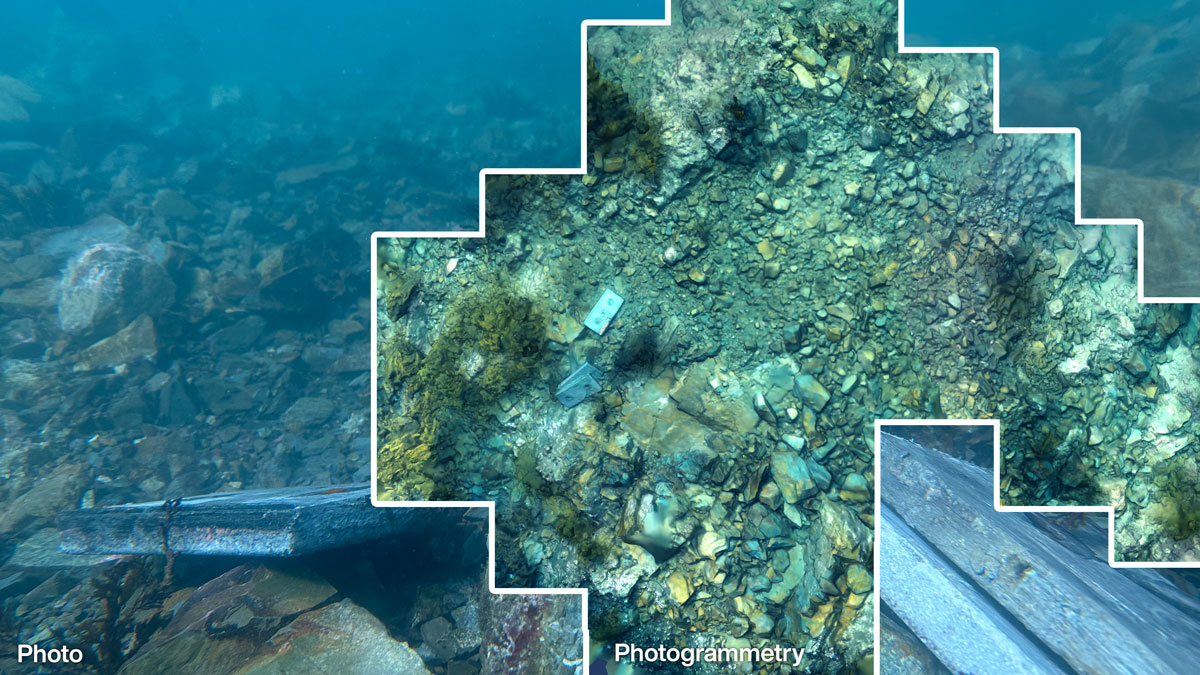

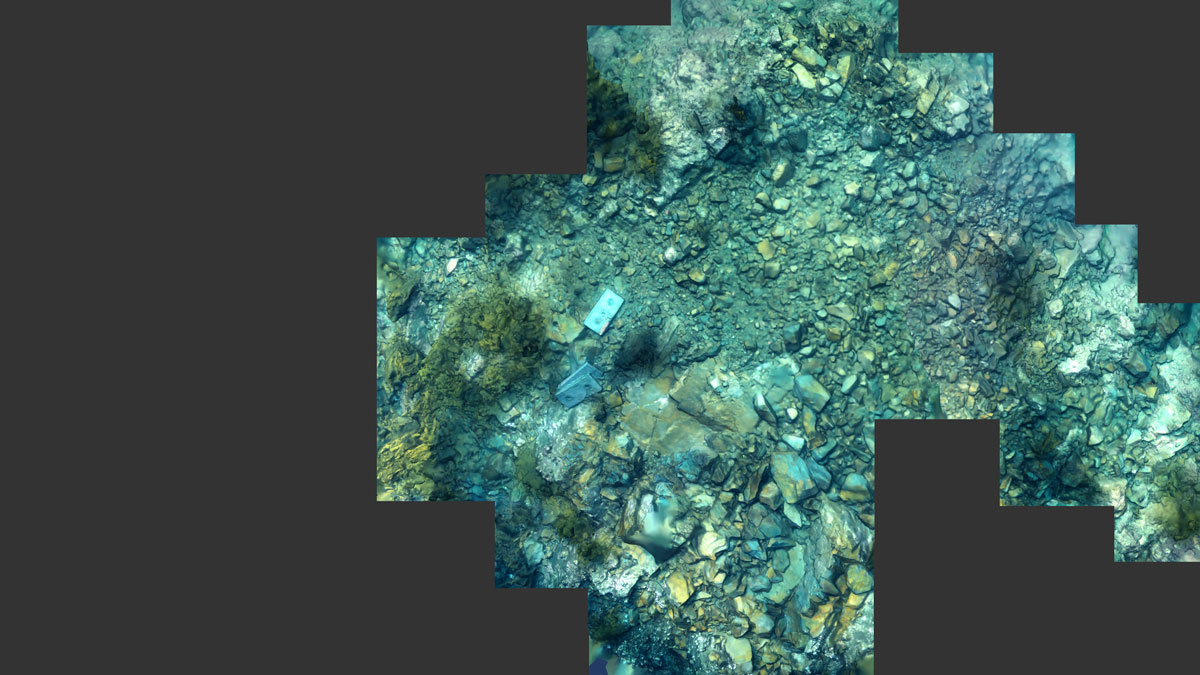

The Harbourmaster, the Coastguard and the Police Maritime Unit responded with impressive urgency to the grounding of the Chokyu Maru No 68 in the Hauraki Gulf on the 16th of April 2024. The 48-meter tuna long longliner struck a reef at the Noises Islands before dawn, yet through fantastic coordination between community and government agencies, was refloated by midday. The next day underwater photographer Shaun Lee visited the site to see what damage had been done. He found a 9m2 gash in the reef where the large ship had made impact with massive force, leaving a tonne of broken rubble. However, it was not the worst damage to be found. The ship had crashed into what several decades ago was a rich shallow reef filled with biodiverse seaweed forests and an abundant marine community. Now a near moon landscape featured in the dive, with little sign of life barring some tattered stalks of seaweed and turfing algae.

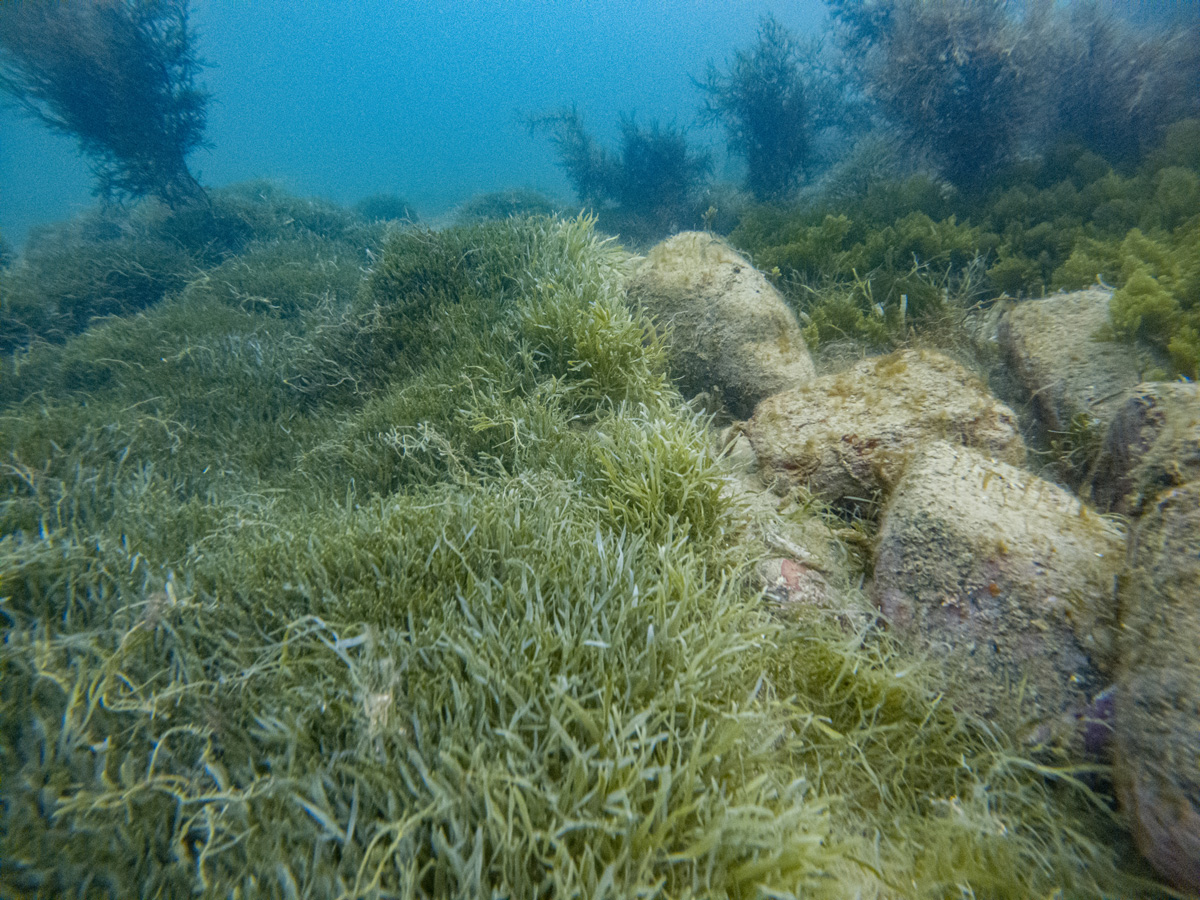

At this site and across the Gulf the seaweed forests that support life are on the way out, eaten by kina / spiny urchins that have exploded in abundance due to the absence of their main predators, large crayfish / kōura and large snapper / tāmure. We, me, you – recreational and commercial fishers have taken those large predators, pulled them from crevices or dragged them out of the water on lines and in nets setting off a trophic cascade, a powerful indirect interaction that is bringing the Gulf ecosystem to its knees.

Unlike the striking and immediate response to a grounded Chokyu Maru which could damage the marine environment with an oil spill, our response to the unfolding ecological crises across the entire Gulf has been disastrously slow. This is despite the community raising the alarm for decades, and Hauraki Gulf Forum State of the Gulf reports explaining the solution. The political response that we are dependent upon to save our Gulf has two main components: the first is the protection of marine habitats, the second to adequately manage fisheries.

Protecting areas to restore top kina predators such as large kōura and tāmure is an obvious action that could turn around the state of the Gulfs barren reefs. Yet it has been seven years since the Sea Change – Tai Timu Tai Pari Hauraki Gulf Marine Spatial Plan was published (itself a three-year process) and the resulting Hauraki Gulf Marine Protection Bill, that could finally see marine protections put in place, is still churning its way through parliament. Indeed, the Noises Islands reef that the ship ran into is included in this bill that is currently before select Environment Select Committee with no guarantees of a successful outcome.

Managing fisheries falls under the Fisheries Act which states that Fisheries New Zealand must manage the adverse effects of fishing on the aquatic environment. A Hauraki Gulf Fisheries Management Plan was signed off in August 2023 to “Facilitate the co-development of a management plan for restoring healthy kelp forests, which will consider the causes and address the environmental impacts of kina barrens and include management considerations for predator species such as tāmure and kōura.” In response the government has announced two measures to address kina barrens including increasing the daily bag limit and proposing a permit system to allow for culling, harvesting or translocating of kina. Both are out for consultation until the 3rd of May and both indicate/suggest a depressing avoidance of addressing the underlying reason the barrens exist in the first place. Neither measure seeks to restore kina predator abundance, the ultimate cause of the barrens. Increasing the daily kina bag limit fails to address the barrens problem as fishers don’t target kina barrens. As Professor Andrew Jeffs (Auckland University) puts it: “kina in barrens don’t taste any good because they are too skinny, waiting in a zombie like state for kelp to return”. Sorry Professor Jeffs, but the kina might be waiting zombie like for some time with this kind of political thinking. The second measure is a proposed permit to harvest, cull, or translocate kina. Kina barren expert Dr Kelsey Miller (Auckland University), who has been experimenting with kina removal, says these methods work but are a temporary fix unless the root cause of the barrens, a lack of kina predators, is addressed. “Where we removed kina, kelp rapidly regrew in high numbers, but unless kina densities are kept low by predators or us, these areas will return to kina barrens”. The Hauraki Gulf Forum has asked for “higher biomass targets for the predators of kina – large tāmure and kōura – and potentially maximum size limits for those predators to allow nature to rebalance itself. This would also have flow on benefits to local communities and fishers through increased abundance of kaimoana”.

The communities of Tāmaki Makaurau are crying out for action on the decline of the Gulf and can only dream of a state of urgency on this issue that matches agency response to the grounding of the Chokyu Maru. Policy director for the Environmental Defence Society Raewyn Peart made the point in her recent submission to the select committee reviewing the Hauraki Gulf Protection Bill “We need a fast-track for the environment”.