The first flights for young black petrels that call the Hauraki Gulf home is an epic OE across the Pacific to South America. But few survive that trip to return to breed as adults.

The big question is why, says Janice Molloy with the Southern Seabird Solutions Trust.

With just 2,700 pairs left, the birds only breed on Aotea/Great Barrier and on Hauturu/Little Barrier. At high risk of being caught on fishing gear, seabird advocates are keen to know more about the young birds travels once they leave our shores, to increase their chances of survival.

“The issue is likely to be the fishing fleets operating off the coast of Ecuador,” says Molloy.

“There are a lot of small artisanal fishing boats in these areas, doing bottom long lining.”

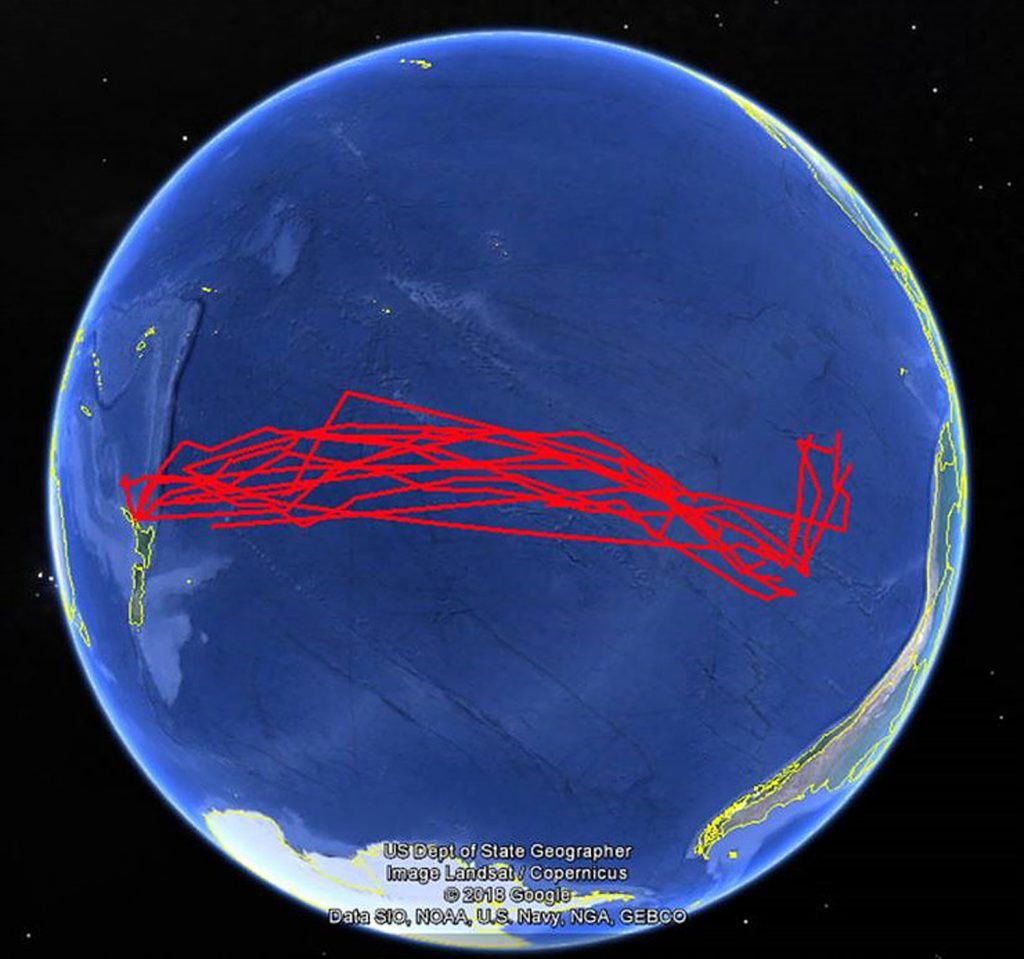

In an effort to understand their epic journey at such a young age, young black petrels have been tracked from their burrows on Mt Hobson, Aotea/Great Barrier Is. on their maiden flight. This huge effort sees them flying almost a third of the way around the planet across the Pacific Ocean, to the Galapagos Islands and the coast of Ecuador. While the tracking exercise doesn’t tell the full story, it suggests most of the birds survive the initial flight from New Zealand.

Samantha Ray and Senior Ecologist, Nikki McArthur of Wildlife Management International had been on Aotea keeping an eye on the birds since the eggs were laid in late 2017.

In early May the pair kitted out 14 of the youngsters with transmitters, to see how they would manage to make the journey. To add to the difficulty of their maiden flight the young birds have to do it without their parent’s guidance, as the older birds leave about two weeks ahead of their chicks.

Soon the birds were off, with varying degrees of skill and grace in getting airborne. Heading off in pretty much the same direction suggests they instinctively know where to go. In just four days the fastest of the birds had travelled 5,000 kilometres, passing south of Pitcairn Is. Then on to Easter Is before heading north along the Peruvian coast toward the Galapagos Islands.

One transmitter died three weeks into the journey, but tracking was possible for many of the birds for much longer than expected.

While the batteries were only expected to last until 12 July, half of the transmitters were still giving off signals three weeks after the estimated “end of battery life.” By 6 August three were still operating showing the birds had averaged a journey of 12,295 km.

Many of the birds seemed content to spend much of their time south of the Galapagos Is, although a few crossed the equator.

There is just one education officer who talks to the fishers in Ecuador’s coastal ports, Molloy says.

While there are significant challenges off the coast for the birds, there may be even bigger problems for those birds at sea.

“Birds that are outside of Ecuador’s exclusive economic zone – on the high seas – come into contact with the really big international fishing fleets,” Molloy says.

“The New Zealand Government, along with environmental groups, will need to get involved, and give support to Ecuador around education.”

This project is possible thanks to support from the Auckland Zoo Charitable Trust.