It’s tough being a NZ fairy tern.

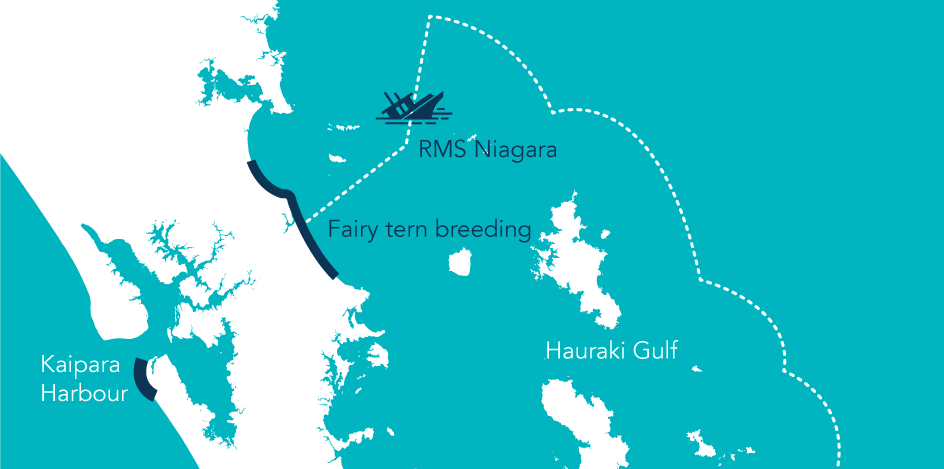

Currently there are only 10 breeding pairs, 40 individual birds, on just four beaches – Waipu sandspit, Mangawhai sandspit and Pakiri River mouth in the Hauraki Gulf and Papakanui sandspit on the southern headland of the Kaipara Harbour.

Until the early 1900s NZ fairy terns or tara iti were widespread, breeding around the coasts of the North Island and at river mouths of the South Island.

Today they are New Zealand’s rarest endemic breeding bird, a decline that can be attributed to:

- Loss of chicks and eggs due to disturbance by humans and their vehicles, dogs and horses.

- Modification of breeding, foraging and roosting habitat by forestry, development and encroaching vegetation.

- Predation by rats, mustelids, cats, hedgehogs, plus by native avian predators, black-backed gulls and Australasian harriers, and possibly red-billed gulls.

- Adverse weather events such as storms and cyclones that can impact productivity each breeding season.

We can add another potential threat to the list, with the oil-bearing wreck of the RMS Niagara lying directly off the 40km stretch of their east coast breeding habitat.

Here is a breakdown of the population leading into the 2017-18 season:

- 4 of last season’s surviving chicks were too young to breed

- 1 spent female, too old to breed

- 1-2 ‘engaged’ couples who behave as a breeding pair, but do not lay eggs

- c. 11 unpartnered males, because of a dearth of females

- 20 breeding birds (10 pairs)

- Waipu 2

- Mangawhai 5

- Pakiri 1

- Papakanui 2

This desperate plight prompted me to print 3D replicas of the birds as a tool for conservation, education and advocacy.

The idea of decoys is not new. Polystyrene fairy terns were first crafted by Darryl Jefferies and used in his experiments in 1999.

Darryl carved his pioneering decoys out of dense polystyrene then painted them in fairy tern breeding plumage.

He conducted 16 trials at Papakanui Spit outside the breeding season and found the models were effective in attracting fairy terns to a specific area (with >80% success). He also found the fairy terns behaviour towards the decoys paralleled live tern interactions – erect postures, one aggressive response and a possible courtship response!

His research in association with Prof Dianne Brunton (Massey University) and published in Animal Conservation, concluded “regardless of whether the attraction of fairy terns towards these decoys encourages residence and nesting in this area, the effectiveness of attracting terns to a specific location results in a safe and efficient means of trapping adults away from the nest and/or outside the breeding season.”

Forest and Bird are using Darryls’ decoys and taped calls to attract NZ fairy terns to restored shell patches which were an historic breeding site on the Kaipara Harbour. They have also been used at roost sites by Birds NZ members to attract fairy terns into open areas where their leg-bands can be easily seen and recorded.

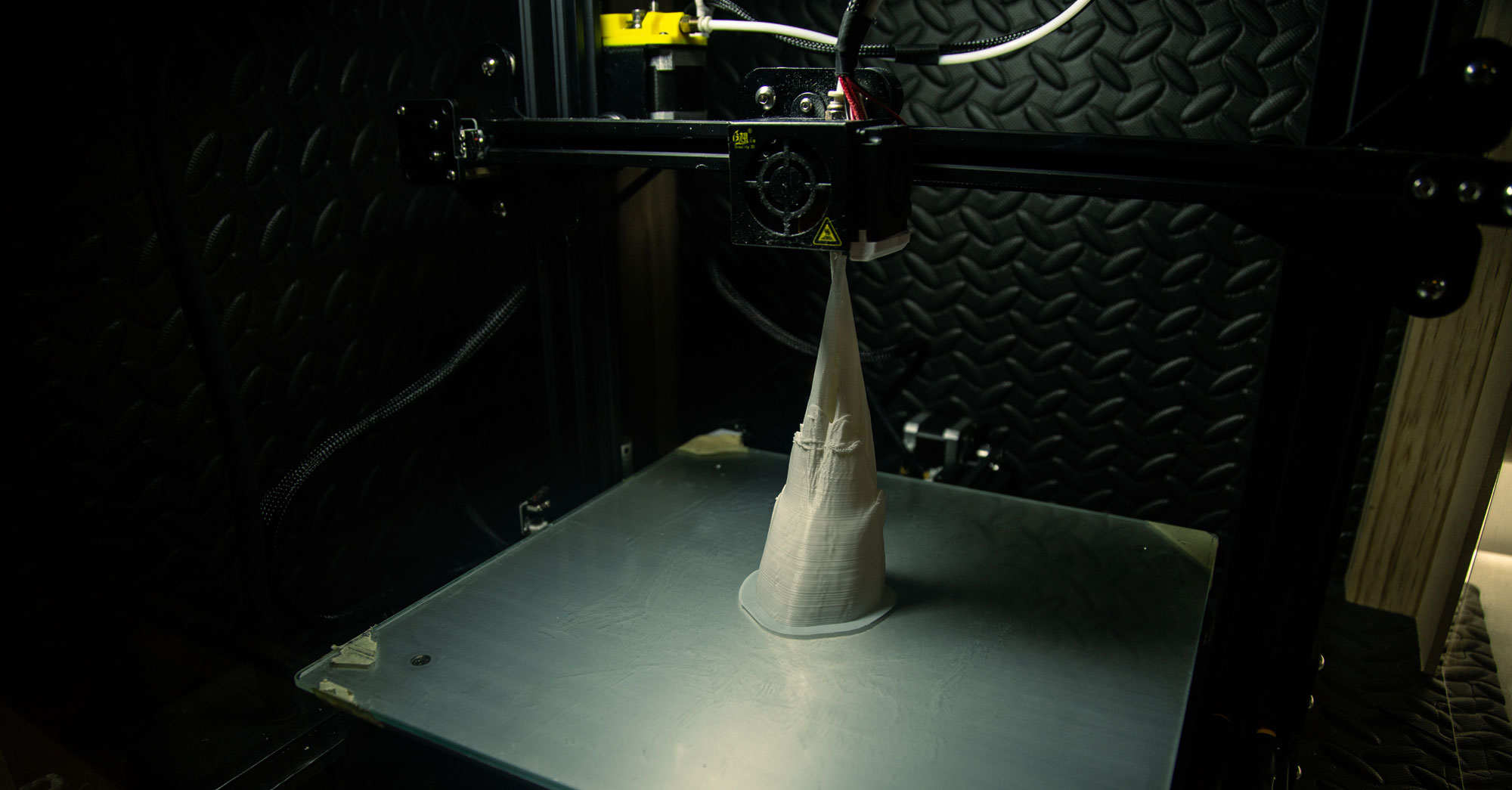

The polystyrene decoys do not weather well so it occurred to me to use new 3D printing technology to create more durable and realistic models. 3D printing is also not new to the New Zealand Fairy Tern Recovery Project. In 2016 the Endangered Species Foundation of New Zealand 3D printed dummy eggs to replace real eggs in nests threatened by storms or cyclones, so they could be artificially incubated at Auckland Zoo.

The 3D printer I purchased for $600 sits on my desk and is powered by solar panels on the roof. It, extrudes PLA (Polylactide) plastic (which is both biodegradable and made from renewable resources) like a robot with a tiny glue gun. Each decoy is made of four parts and it takes about 16 hours to print them all.

Needing the exact dimensions of NZ fairy tern, something photos don’t provide, Auckland War Memorial Museum kindly allowed me to examine a mounted NZ fairy tern specimen they have in their collection, which also helped with colour matching. Then I hand painted various seasonal plumages and a juvenile bird based on drawings by Gwenda Pulham and photos from Susan Steedman.

Each decoy for use in the field is mounted on a large spike which can be pushed into the beach. The decoy pivots on the spike (like a wind vane) and therefore always faces into the wind, just as real NZ fairy terns do when roosting or incubating.

I haven’t yet tested them in the presence of NZ fairy terns but a beach trial did attract the attention of a white-fronted tern.

I imagine they could be useful in luring an injured (or partially oiled) NZ fairy tern into a catchable situation? And I am now suppling the 3D printed decoys to organisations who are helping the NZ fairy tern’s chances of survival.

Because most New Zealanders have never seen a real NZ fairy tern, these life-like replicas could well play a role in education and advocacy for this endearing little bird.

Information coutesy of nzbirdsonline, Birds New Zealand members, Darryl Jefferies, Auckland War Memorial Museum, Forest and Bird, and I thank Gwenda for her time.